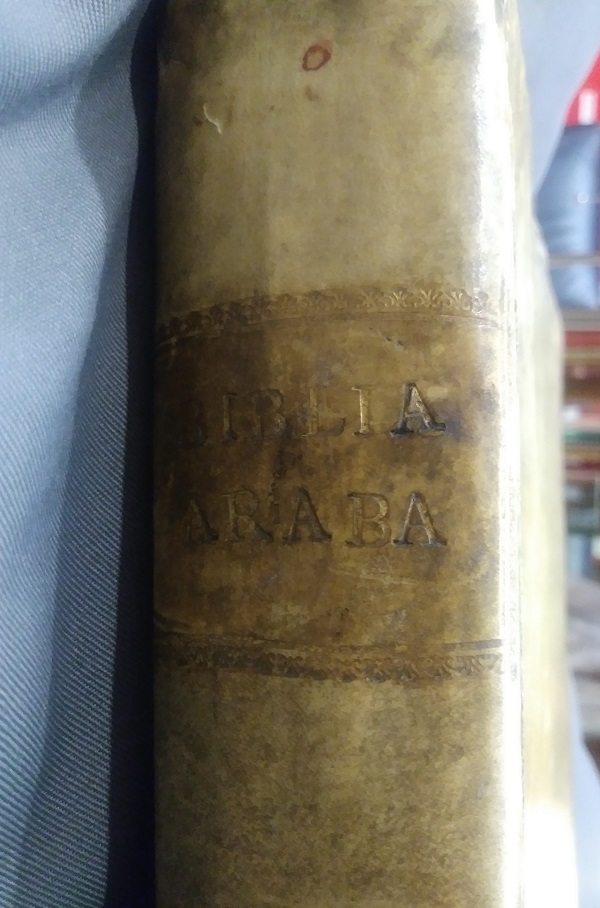

Spine with title: Biblia Araba

Arabic script with interlinear Latin: section division

Saint Mark the Evangelist with his winged lion

Bashārat Yasuʻ al-Masīḥ kamā kataba Mār Mattay waḥid min ithnay ʻashar min talāmīdhihi = Euangelium Iesu Christi quemadmodum scripsit Mar Mattheus unus ex duodecim discipulis eius, 1591

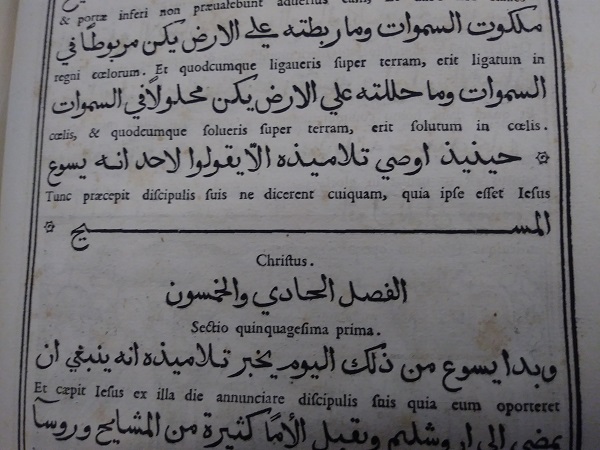

The Gospels in Arabic with interlinear Latin, produced by the Typographia Medicea (also known as the Medici Oriental Press) in Rome. This 1591 edition used the same Arabic text as the press’ Arabic-only edition the year before, which had been the editio princeps of the Gospels in that language. The Latin text was added, but the book design remained the same – page-order arranged for reading right to left, same woodcut illustrations distributed throughout. The Arabic type was designed by the French typographer Robert Granjon, the text was edited by Giovanni Battista Raimondi (who ran the press), and the woodcuts were designed by Antonio Tempesta and engraved by Leonardo Parasole.

The Typographia Medicea was established in 1584 in Rome under the patronage of Cardinal Fernando de’ Medici and this was its first production. Under Raimondi’s guidance, the press produced Christian, secular scientific works, and grammars in Arabic. The books were designed for sale in both Europe and in the Islamic East. Unfortunately, the venture was not financially successful. Raimondi claimed the books were printed in order to help convert Muslims to the Christian faith, but scholars suggest that they were perhaps targeted to multiple audiences, including Christians living in Islamic lands and European scholars hoping to learn Arabic.

The typography, one of the earliest Arabic scripts used in European printing, was praised by contemporaries. The woodcut blocks were discovered later and became the subject of a comparative study with the printed books by the scholar Richard S. Field. Even though the Gospels in Arabic and Latin were not commercially successful, Robert Jones has argued that they, along with the rest of the output of the press, helped spark the development of Arabic studies in Europe in the seventeenth century and beyond.

The UCLA Charles E. Young Research Library Special Collections copy is bound in vellum, with red and blue mottled edges and the title “Biblia Araba” stamped in gold on the spine surrounded by a thin decorative border. Some pages show discoloration inside (ex. pages 364-365).

The text begins on a page numbered “9” – the first page of the Gospel of Matthew – without any front matter. It ends on page 462, followed by an unnumbered page with a note to the reader in Latin identifying some errata and the colophon which reads “Romae : In Typographia Medicea. M.D.XCI.” Each page has the text inside a border made out of two thin black lines, first line in Arabic script followed by the Latin in roman type, then alternating. Illustrations are inserted into the text intermittently, with various page positions, often separated from the text above and below it by another border of just one line. Sometimes there are two illustrations on one page. There are numbered sections throughout each Gospel. Occasional headpieces and ornaments appear on the pages (ex. page 227).

The pages proceed right to left, with both Arabic and Latin running headers with page number and Gospel (Matthaeus, Marcus, Lucas, or Johannes). Within the page, the Arabic text runs right to left, while the Latin runs left to right. Each Gospel begins with a woodcut illustration of the Biblical Evangelist for which it is named, with each depicted writing and accompanied by iconographic symbols to identify them. Other illustrations depict scenes from Jesus’ life, with many repeated between, and some within, each Gospel. Between pages 360 and 361 the cords can be seen and the same woodcut is repeated on both facing pages. Some illustrations have either the designer’s or the engraver’s initials (or both).

References

Robert Jones, "The Medici Oriental Press (Rome 1584-1614) and the Impact of Its Arabic Publications on Northern Europe." The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England. ed. G.A. Russell, pp. 88-108.(Leiden: Brill, 1994).

Study of the reception and influence of the Arabic Gospels and the Medici Press

Richard S. Field, "Antonio Tempesta’s Blocks and Woodcuts for the Medicean 1591 Arabic Gospels" (Chicago: Les Eluminures, 2011).

Catalogue describing and analyzing recently-discovered woodcut blocks used in the printed Arabic-Latin Gospels.

Evelyn Lincoln, "Gospel Lessons: Arabic Printing at the Tipografia Medicea Orientale." Art in Print 4:4 (Nov.-Dec. 2014). Online.

Examination of Medicea Arabic-Latin Gospels' publishing history

This spotlight exhibit by Rhonda Sharrah as part of Dr. Johanna Drucker's "History of the Book and Literacy Technologies" seminar in Winter 2018 in the Information Studies Department at UCLA.

For documentation on this project, personnel, technical information, see Documentation. For contact email: drucker AT gseis.ucla.edu.