The Wonderful, Horrible

Films of Paul Verhoeven

by Dan Streible

How

do you tell a fascist film? Or

does it matter anymore? Can a

contemporary Hollywood movie traffic in both Nazi iconography and fascistic

philosophy and still pass as harmless entertainment, noted only for its great

special effects and its use of more rounds of ammunition than any film in

history? And is the presence of

"men with guns" a required signifier for a film either to encourage a

fascist point of view or to be symptomatic of a culture listing to the right?

Such

questions were raised in 1997 with the well-hyped release of Paul Verhoeven¹s

$100 million adaptation of Robert A. Heinlein¹s 1959 ³classic² science fiction

novel Starship Troopers.

All of the films Verhoeven has directed since his arrival in Hollywood

have generated controversy. His

work has alarmed cultural guardians with its extraordinary levels of gruesome

violence [Robocop (1987), Total Recall (1990)] and graphic sexual

exhibition [Basic Instinct (1992), Showgirls (1995)]. Comparatively, however, Starship

Troopers received only a modicum of critical chastisement. This despite the fact that -- in

addition to the gory, flesh-ripping gunplay -- the film offers up what its

producers called a ³fascist utopia.² [1]

Its top-gun, teenage warrior-heroes are showcased in a glossy display,

steeped in Nazi aesthetics. They

embrace a rousing militarism that deems democracy a failure and a martial state

a success. Our young S.S. Troopers

casually but willfully endorse the ideals of the Federation that teaches them

"violence is the supreme authority." In short, under Verhoeven¹s helm, the position affirmed by

all of the principal characters fails to differentiate itself sufficiently

from, say, the ideology espoused by certain well-known orators captured on film

in Nuremberg in September of 1934.

A major studio release that doesn't just allude to, but looks, talks,

and walks like Triumph of the Will (Leni Riefenstahl, 1935)?

The

release of Starship Troopers prompts a renegotiation of the critical

debate around the issue of incipient fascism in contemporary Hollywood

cinema. The film also represents a

distressing shift in the ability of Paul Verhoeven to intervene from within the

system as a potent postmodernist who makes blockbusters that knowingly ridicule

the violent, action extravaganza mentality. Rather than critiquing such projects, Starship Troopers

falls into a political incoherence that potentially enables viewers to

entertain the idea of a fascistic military state as a viable future. While the machine gun and other

firepower remain fetishized in the imagery of this high-tech movie, men with

guns do not necessarily rule the day.

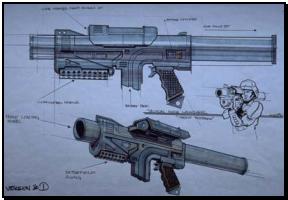

The "Morita"[2] rifles the troopers wield against hostile

alien insects allow them to display a degree of bravado and power on the

battlefield, but their guns do not win the war. In a cinematic age in which Texas-sized meteorites bombard

the earth, guns ultimately become a symbol of impotence rather than power. However, in Starship Troopers

this decline of the gun's dominion does not indicate a failing of the future

warrior-state. Rather the film

suggests that power derives from the lens of a camera rather than the barrel of

a gun. The power of fascist force

comes less from its military superiority than its ability to captivate minds

with its commanding, monumental imagery, its corporative ability to create

group-think.

Given

the troubling political

implications of Starship Troopers, I¹d like to examine how such a film

came to be, how it was positioned for reception and how it was received. My conclusions are based on an

examination of movie trade journals, promotional materials, journalistic

reviews, and on-line discussions -- both critical and fan-based. As secondary resources I consider Starship

Troopers in the light of what critical film studies have previously

suggested about cinema and fascism.

The key text remains Susan Sontag¹s 1974 essay ³Fascinating Fascism,²

which sought to define the aesthetic markers that abetted fascist, or at least

Nazi, art as evident in the work of Leni Riefenstahl.[3]

Also

important is the way in which Verhoeven figures into the symptomatic readings

of key films from Reagan-era Hollywood, particularly those by critics such as

Robin Wood, Michael Ryan, Douglas Kellner, David Denby, Susan Jeffords, Stephen

Prince and others. Their

perspective has noted how both patently conservative films (Red Dawn,

Rambo, Schwarzenegger vehicles) and mainstream fantasies (the Star Wars, Rocky,

and Indiana Jones series) betrayed tendencies that had disturbing parallels

with fascist culture.

"Vengeful patriotism, worship of the male torso,"

"military spectacle" and weapons of overkill were making U.S. commercial

cinema into a showcase for what J. Hoberman called in 1985 "The Fascist

Guns in the West."[4] In the

decade following, Hollywood continued in a similar vein, with big-budget

spectacles ranging from Bruce Willis action pictures to jingoistic sci-fi

shootouts like Independence Day (1996). Yet cries of fascism diminished

in critical circles. This was also

a period when Verhoeven directed his acclaimed Robocop and the dense,

complex Total Recall -- two conspicuous blockbusters that retained the

big guns and special effects while seeming to subvert the political inflections

of the genre.

Given

this context, the contradictions of Starship Troopers require

explanation. How did a Hollywood

film with such in-your-face fascist imagery appear at a time when concerns over

quasi-fascist tendencies in popular cinema had become muted? Does the film undo Verhoeven's previous

reputation as a thoughtful if audacious social commentator?

Inside the Cabinet of Dr. Verhoeven

We

must begin by reading Starship Troopers as part of the ³wonderful,

horrible² films of Paul Verhoeven.

I appropriate the title of Ray Müller¹s insightful documentary film

about Leni Riefenstahl because Verhoeven seems a parallel enigma to her: an auteur full

of self-contradiction whose work invites polarizing analyses, an artist who

avows provocative artistic creation while disavowing political intention or

social responsibility.[5] In the

1990s, Verhoeven became a bête noire, the director of

horrible excess who pushed the limits of MPAA-approved violence and sex. Yet his films remain wonderful enough

-- in box office terms and in stylistic distinctiveness -- to keep him on the

major studios¹ A-list. In the

1980s, he also was lauded by analysts of pop culture politics. Retaining the edge of his Dutch films,

Verhoeven was credited with critiquing the retrograde aspects of the Hollywood

action blockbuster by making ultraviolent, effects-laden fantasies that

ridiculed the conservative, militaristic ethos of Rambo and his cohort. If Sylvester Stallone could blow away

his enemy with force of arms, Verhoeven would paint a world in which everyone

was subject to gunfire. Like the

Dutch masters of old, he put the anatomies of corpses on display. But his bodies were ripped by disorderly

bullets, not scientifically vivisected by surgeons. [6]

Stephen

Prince's perceptive book Visions of Empire (1992) epitomizes the

critical valorization of Verhoeven.

Prince discusses the director's work as part of a "dystopia

cycle" of movies that countered the conservative trend in eighties

Hollywood. Arguing that such films

confront issues of political exploitation, corporate control and resistance to

police-state coercion, he says such ideas "receive their most intelligent

and deliberate working out" in Verhoeven's Robocop and Total

Recall, the cycle's "two most outstanding exemplars." Prince calls the former a "grim

indictment of Reagan policies" that is nothing less than " a thinking

person's action film whose politics are left of center." Like other admirers of the movie, he

interprets its satirical humor as granting viewers "the Brechtian distance

necessary to see ties between their world and the film's future." While Total Recall is a more

compromised critique, it remains a "cautionary fable" that becomes

"one of the subtlest but most critical imaginative transformations of the

political referents of the Reagan period." Arnold Schwarzenegger's

proletarian hero of the future is a rebellious freedom fighter who overthrows a

villainous corporate state (headed, as in Robocop, by a perfectly evil

boss played by Ronny Cox). In

Prince's estimation "one feels that Verhoeven would have gone much

farther" in his political critique if not for the constraints of

commercial production.[7]

Certainly

one does not "feel" this when watching Starship Troopers. The cinematic provocateur, earlier

hailed as a subversive satirist, instead made a movie that flirts closely with

fascist ideas and images. He seems

quite an unlikely candidate for such work. Or such were my impressions after spending a day with the

director in November 1995.

Although his inglorious Showgirls had just been released, he made

good on his pro bono offer to meet with film students. With a Ph.D. in mathematics, Dr.

Verhoeven was at home in the academic environment. He was engaging, bright, and unpretentious. He was glad to engage in debates about

civil liberties, sexuality, censorship, art and morality. Clearly he took his work seriously,

even if he was too often vague about why he engaged in such controversial types

of representation. (Often he would say only it was because ³that interests

me.²)[8]

Two

items of relevance here arose during this encounter. First, Verhoeven described his preproduction for a

big-budget, big-bug film called Starship Troopers, which had been

greenlighted solely, on the basis of a short sample of computer-generated giant

insects done by special effects artist Phil Tippett. Second was his frequent reference to his World War II childhood

experiences as an explanation for his comfort level with violence and

dismembered bodies. Born in

Holland in 1938, he was socialized, he said, into a world where seeing Nazi

invaders drag off the Dutch dead was commonplace.

With

this in mind, Verhoeven¹s rendering of ³fascism lite² -- as Der Spigel

called it[9] -- is all the more surprising and disconcerting. Why would a recipient of Nazi

aggression make a film which permits a reading of fascism as a possible future

that "works"? Even

Verhoeven¹s earliest cinematic credentials seem solidly anti-fascist. After learning filmmaking in the Dutch

military (like Heinlein he was a Navy man), he made Mussert (1968), a

documentary about the head of the Netherlands¹ Fascist Party during World War

II. Soldier of Orange

(1979), which led Steven Spielberg to invite Verhoeven to Hollywood, is his

historical drama about Dutch resistance fighters who take on Nazi

collaborators. Far from lionizing

fascistic ideals of order, monumentalism, virile posing and perfect bodies,

Verhoeven¹s Dutch films undermine such values. His down-and-dirty seventies films are more at home with the

work of the ³degenerate² artists condemned by the Nazis. Irreverent, messy, vulgar. They also demonstrate sympathy for the

outsider. The bohemian sculptor in

Turkish Delight (1971), the gay writer in The 4th Man (1979), and

the disenchanted motorcycle riders of Spetters (1980) are a far cry from

the cardboard supersoldiers of Starship Troopers.

Yet

his futuristic war extravaganza was consistent with the turn Verhoeven took

when he came to Hollywood. Since Robocop,

his films have been marked by their excessive high gloss, splashy spectacle,

and intense action. Each contains

set pieces calculated to outrage middle-class sensibilities. Many turn disturbingly comical in

tone. In Robocop, we see

police officer Murphy tortured by drug dealers who make a game of shooting off

his hands and arms. After he is

resurrected as a cyborg, his first turn in crimefighting is to use his

laser-accurate pistol to shoot a would-be rapist in the genitals. In Total Recall, the rebel hero

fights off a series of machine-gun assaults, memorably using a human corpse as

a bullet-absorbing shield. Basic

Instinct¹s infamous opening features an explicit sex scene that culminates

with an icepick murder at orgasm.[10]

Starship

Troopers¹ deliberate flirtation with fascism, therefore, might be

understood as just another wrinkle in the Verhoeven career: ironic deployment of dizzying violence,

cold characters, outrageous political philosophy and allusion to Triumph of

the Will -- all merely for the sake of provocation. However, this excursion into the

postmodern politics of irony differs from its predecessors. Its irony is so "blank" that

it can invite readings as a text that seems neo-nazi itself.

Fascism Light and Magic

How

might a film be deemed "fascist" a half-century after Hitler? Does Troopers belong in this

category? In the broadest sense,

this special-effects fantasy is merely a part of the post-Star Wars

"cinema of oppressive spectacle" of which so many critics (liberal,

conservative, humanist) have complained.

David Mamet, for example, spells it out in a lesson on screenwriting.

We,

as the audience, are much better off with a sign that says A BLASTED HEATH, than

with all the brilliant cinematography in the world. To say "brilliant cinematography" is to say

"He made the trains run on time."

Witness

the rather fascistic trend in cinema in the last decade.

Q. How¹d you like the movie?

A. Fantastic cinematography.

Yeah,

but so what? Hitler had fantastic

cinematography. The question we

have ceased to ask is ³What is the brilliant. . . cinematography in aid

of?²[11]

So

it is with Troopers. The

giant bugs look cool. The effects

are fantastic. But so what?

As

cultural historian Russell Berman argues in his analysis of fascist form, Triumph

of the Will exemplifies the ³fascist privileging of sight and visual

representation² because fascism

"transforms the world into a visual object, ... the spectacular landscape

of industry and war.²[12] Thomas

Elsaesser points out in his assessment of Nazi-era commercial cinema, however,

this matter can be overly stressed.

To take this Frankfurt School view is ³to propose that all popular cinema is potentially fascistic, if by this we mean

illusionist, . . . using affect and emotion to overpower reason."[13] Clearly both Triumph and Troopers

stand to abet a fascist politics with their visual objectification of masses,

their overwhelming cinematography.

But to lump them together with Brazil

(Terry Gilliam, 1985), Metropolis (Fritz

Lang, 1926), 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968), Contact (Robert

Zemeckis, 1997), or Apocalypse Now (Francis Coppola, 1979) is to lose

their more particular political meanings.

A

discernment of fascist tendencies in recent cinema also occurs in Robin Wood¹s

reading of Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan. Wood identifies ³Fear of Fascism² as part of a

Spielberg-Lucas "syndrome," the potential for America to become a

totalitarian state, for the individualist American hero to become

indistinguishable from the fascist one, for the weak-minded to be taken over by

a Vader-ian Force. Although George

Lucas¹ well-known reference to Triumph of the Will is more discrete than

Verhoeven¹s, Wood suggests that its presence in Star Wars is more than

just a joke. The thrill of the

Jedi military victory and the spectacle of triumphant troops assembled at the

movie¹s conclusion resonate with authoritarian overtones. He also reminds us that, historically, fascist cultures did not feed on

overtly political propaganda films but on light entertainment that reinforced

certain conceptions of the body, national identity, family, etc. Rocky Balboa and Indiana Jones are not

protagonists in fascist films, but would be at home in a fascist popular

culture.[14]

Starship

Troopers puts fascist ideas on the table more explicitly than the

Spielberg-Lucas films. Indiana

Jones still knows a Nazi when he sees one. And he opposes them unambiguously. On a manifest level, these films don't encourage an

understanding of a Nazi enemy -- however cartoonish -- as anything other than

Other. Verhoeven¹s futuristic

fantasy treads on this dangerous ground by reversing this, inviting us to

identify with the fascist protagonist.[15]

To

be more historically precise, we can define fascism as a political and social

system marked by authoritarian

rule, military force, intense nationalism, expansionist conquest, demand for

racial purity, the rhetoric of new order,¹ supremacy of the state, and

obedience to a charismatic leader (the one element absent from ST). It values martial discipline,

sacrifice, surrender of individual will to social order, glory in combat and

death, youthfulness and a cult of the body sans eros. None of

these alone is unique to fascist philosophy and I am not suggesting that

Verhoeven is advocating them. But

in bringing Heinlein¹s novel to the screen, he creates a cinematic space where

they are allowed to play amid a riot of Nazi mise-en-scene.

Heinlein¹s

book, as even its cult of fans admit, lacks strong plot or character

development. It is remembered for

its provocative political soapbox, in which the author argues for a

conservative-libertarian social order built by virile citizen-soldiers. The book itself is often labeled a

fascistic fantasy.[16] Despite the

novel¹s formal weaknesses, screenwriter Ed Neumeier (who also wrote Robocop)

retained its comic-book plot and pared down the philosophizing.

Johnny gets his Gun

Starship

Troopers combines Heinlein¹s sci-fi war story with a Melrose-dramatic teen

love triangle. Four friends are

graduating from a high school in a futuristic Buenos Aires that looks

suspiciously like a Los Angeles suburb.

All enlist in Federal Service:

our dumb-jock hero, Johnny Rico does it for his brainy-beautiful

girlfriend Carmen Ibañez, who goes to Flight Academy. Nerdy best friend Carl goes into military intelligence,

while smart-jock Dizzy Flores gives up her career as a pro football quarterback

to follow her beloved Johnny into the Mobile Infantry.  Johnny is about to quit boot camp when Giant Bugs drop a meteor on

Buenos Aires, killing millions.

Johnny¹s platoon of gung-ho roughnecks are led into battle by their high

school civics teacher, Mr. Rasczak.

The battle for planet Klendathu is a fiasco, with troopers with their

World War II style machine guns prove no match for the deadly arachnids. A second battle ends in victory thanks

to Rico and Diz¹s sharpshooting and our hero¹s cowboy tactics with mini-nukes. The comrades-in-arms celebrate by having

sex, Johnny finally giving in when the eugenically-minded Moral Philosopher Lt. Rasczak instructs

him to procreate. Finally comes an

apparent suicide mission to Planet P, home of the giant Brain Bug. In a scene reminiscent of the Alamo, we

watch from inside the barricaded fort as millions of bugs swarm over the

fortress walls. Diz and Rasczak

die gruesome but heroic deaths, impaled by insect claws, before Carmen¹s fleet

arrives to save Johnny. During a

second attack, Carmen is captured and about to have her skull sucked dry by the

Brain Bug when Lt. Rico saves the day.

We end irresolutely, as Colonel Carl appears -- dressed in full Goebbels

regalia. He mindmelds with the

captured Brain Bug and, with a cruel smile, reports ³It¹s afraid!² Thousands of uniformed troopers,

looking ever so much like an army of ants, mindlessly cheer the fear in their

enemy. (³Fascist art glorifies

surrender, it exalts mindlessness,² Sontag observes.)[17]

Johnny is about to quit boot camp when Giant Bugs drop a meteor on

Buenos Aires, killing millions.

Johnny¹s platoon of gung-ho roughnecks are led into battle by their high

school civics teacher, Mr. Rasczak.

The battle for planet Klendathu is a fiasco, with troopers with their

World War II style machine guns prove no match for the deadly arachnids. A second battle ends in victory thanks

to Rico and Diz¹s sharpshooting and our hero¹s cowboy tactics with mini-nukes. The comrades-in-arms celebrate by having

sex, Johnny finally giving in when the eugenically-minded Moral Philosopher Lt. Rasczak instructs

him to procreate. Finally comes an

apparent suicide mission to Planet P, home of the giant Brain Bug. In a scene reminiscent of the Alamo, we

watch from inside the barricaded fort as millions of bugs swarm over the

fortress walls. Diz and Rasczak

die gruesome but heroic deaths, impaled by insect claws, before Carmen¹s fleet

arrives to save Johnny. During a

second attack, Carmen is captured and about to have her skull sucked dry by the

Brain Bug when Lt. Rico saves the day.

We end irresolutely, as Colonel Carl appears -- dressed in full Goebbels

regalia. He mindmelds with the

captured Brain Bug and, with a cruel smile, reports ³It¹s afraid!² Thousands of uniformed troopers,

looking ever so much like an army of ants, mindlessly cheer the fear in their

enemy. (³Fascist art glorifies

surrender, it exalts mindlessness,² Sontag observes.)[17]

As

the absurdity of the plot reveals, Verhoeven¹s film is highly ironic and often

satirical. Heinlein¹s high-minded

patriotism vanishes. And yet. .

. what is this irony is aid

of? Why do we

fight? In whose army do these

soldiers march? (an army whose sergeants insist ³Your weapon is more important

than you are!²) While Verhoeven¹s

adaptation undermines Heinlein¹s right-wing homily, it fails on three

fronts. Starship Troopers

wallows too deeply in Nazi iconography, enjoying its "fascinating

fascism"; it presents a

narrative in which a fascist future works, with no suggestion of resistance or

alternatives; and, most

egregiously, it targets an audience of teens and children, offering them the

possibility of making a positive identification with the film¹s young fascist

heroes.

The

Speerian mise-en-scene is persistent.

The imposing black eagle icon of the Federation mimics the first image

seen in Triumph of the Will.

Uniforms reference the brown-shirt style as well. The set design of the military camps

and Federation architecture imitate what Sontag described as the Deco fascist

style with its ³sharp lines and blunt massing of material, its petrified

eroticism.²[18] Asked about the

Nazi aesthetics, Ed Neumeier said simply, ³the Germans made the best-looking

stuff. Art directors love

it.² Verhoeven added, ³I just

wanted to play with these [Nazi images] in an artistic way.² His play includes more direct

references. The film¹s opening

sequence -- a recruitment ad -- ³is taken from Triumph of the Will,² the

director told Entertainment Weekly. ³When the soldiers look at the camera and say, I¹m doing my

part!¹ that¹s from Riefenstahl. We

copied it. It¹s wink-wink

Riefenstahl.²[19]

Neumeier¹s

script begins and ends with the mocking description ³Proud YOUNG PEOPLE in

uniform, the bloom of human evolution.²

In casting, Verhoeven tries to have things both ways, playing with

fascist aesthetics to subvert them, but managing to privilege a racial type. This is most apparent in the lead

role. Heinlein¹s Juan ³Johnnie²

Rico was a Tagalog-speaking Filipino cum Federation (read: American) citizen-soldier. The movie Johnny and his

Spanish-surnamed girlfriends are supposed to be Argentinean (because this is

where Perón harbored old Nazis?)[20]

But the actors in these roles are quite white, including lead Casper van

Dien, the next screen Tarzan, whose Dutch name resonates with van Damme

macho. The soldiers in Rico¹s

platoon reference the WWII combat film's generic melting pot, updated for a

multicultural future. But even the

characters bearing Jewish, Polish, Japanese and African-American names have the

same fair, too-pretty, idealized faces.

This was not lost on reviewers, who noted the ³Aryan Spelling,²

square-jawed, big-teeth, big-lips uniformity.[21]

Where¹s Johnny?

Even

Verhoeven¹s nod to a gender-neutral military fails to undercut the fascist

ideal. These full-blooded men and

women shower together without sexual attraction, conjuring up the fascist cult

of the body as an instrument of combat rather than eros. As in Riefenstahl¹s film, showering

together demonstrates Spartan camaraderie. In the other notable scene of bodily display, Johnny¹s

hairless torso is flogged in the public square, taking the scars that mark him

as a true warrior. Again Sontag¹s

litany of fascist motifs is borne out:

the ³choreographed display of bodies,² ³physical perfection of beauty,²

³virile posing,² the ³endurance of pain,² the ³exhibition of physical skill and

courage.²[22]

Wink-Wink Riefenstahl?

As

Starship Troopers overindulges its Nazi imagery, it does so in a

narrative universe where a fascistic mentality operates without

disruption. The rules are laid out

for us in Mr. Rasczak¹s valedictory lecture on History and Moral Philosophy. As others have observed, this scene in

which a teacher inspires wartime enlistment takes the anti-war All Quiet on

the Western Front (Lewis Milestone, 1930) and stands it on its

head.[23] The one-armed veteran

explains to his class why military forces had to impose this new world order

after too much democracy led to chaos.

Things "work" because only those who have done state service

are enfranchised. Veteran soldier-citizens are licensed to reproduce. Mere ³civilians² lack ³civic virtue² and can not

vote. Force is the supreme

authority. The rabidly

anti-intellectual, anti-bourgeois side of fascist philosophy is projected onto

the only civilian characters in the film, Johnny¹s rich parents. They discourage their son from becoming

cannon fodder and insist he go to Harvard. Their soft liberalism earns them a spot on the Bug Meteor¹s

fatality list -- weak naïfs, like the people of Hiroshima, says Rasczak.

Accepting

his teaching unproblematically, all sign up for military service. Comradeship replaces family. Youth are socialized into these values

via the greatest of inculcation devices:

football. As star athletes,

Diz and Johnny become the leaders in battle. Here Verhoeven's irony is subdued for a change, not

counterposing high school football fever with zealous militarism the

heavy-handed way Peter Davis does in the anti-war documentary Hearts and

Minds (1974). This is the

principal problem with the Starship Troopers. Verhoeven¹s irony becomes so manic as to become

incoherent. Is he ridiculing

everything? and thereby nothing? When Johnny and friends adopt this

fascistic ideal, at what point does the viewer decide to go along for the ride?

In

his defense, the primary way Verhoeven tries to subvert the Federation¹s

ideology is by replicating the satirical framing device used in his earlier

films. Just as Robocop

intercuts scenes of mock newscasts (showing, a Reagan-figure accidentally

zapped by his own Star Wars weapons), Troopers features a running

propaganda broadcast viewed in an interactive Web-TV format. An ³Official Voice² presents vignettes

about how and why to fight the insect menace.

Does

this lend sufficient critical distance?

Perhaps for adult viewers, the excess, absurdity, irony, and satire make

it clear this is no endorsement of a fascist future. But the conventionally character-driven plot remains in

place with some expectation that viewers will identify with the hero¹s

strivings. Unless one is willing

to root for the horrific, scabrous bugs, the film offers no points of entry

other than the wonderful, horrible protagonist. Verhoeven is consistently anti-humanist, but his film is

confused about what it wants to articulate about fascism.

In

the promotional book, The Making of Starship Troopers, Verhoeven speaks

directly about the subject. At

times he hints at sympathy with Heinlein¹s philosophy, calling it ³benign

fascism.² When pushed to defend

himself, he avers his film is ³subversive,² decidedly not

fascist. But in between he

is as contradictory as his film.

He will only say that a Pat Buchanan-like cryptofascism in the U.S. in

the 1990s is ³interesting,² rather than alarming or wrong-headed. When the FedNet¹s official voice

repeatedly asks ³Would you like to know more?² Verhoeven maintains his film is asking its audience to consider

the nature of such a world.

[I¹m] not saying that ST ¹s society is wrong because of that resemblance

[to the Third Reich]. . . .

These references say, ³Here it is.

This futuristic society works on this level well -- and it fights the

giant insects very well. Look and decide. The judgment is yours.²[24]

Guns R Us

What

audience, then, does Starship Troopers recruit and address? If it were only Heinlein readers

(including all U.S. Marines, who are required to read ST)[25] there

might be less reason for concern.

Most of the author's fans rejected the movie as a disservice to the

book. Verhoeven¹s coldness and bad

taste also turned off many film reviewers. Those who were ready to give him the benefit of the doubt

sometimes addressed the f-word head on, particularly the Washington Post,

in a series of sharp critiques.

But more typical were puff pieces on the film's brilliant cinematography

and cheerleading reviews, such as one the Detroit Free Press headlined

with ³Starship Troopers¹ Sucks Out

Our Brains -- and It Feels Great.²[26]

However,

we must deal with the fact that idealized Brechtian spectators and historically

knowledgeable postmodernists were not the film's main patrons. The Troopers audience (both

actual and constructed) was largely "juvenile," to use the somewhat

dated industry term. If critical

perspective and sophistication are required to read subversive irony, then what

interpretive position is left for those too inexperienced to discern this? Verhoeven¹s film was heavily promoted

to teen and pre-teen audiences with television ads on kids¹ cable, interactive

cyberspace games, an official comic book adaptation, trading cards, a CD-ROM, a

soundtrack album, Toys R Us action figures and weapons ("for ages 4 and

up"),  not to mention the Disney imprimatur. The film¹s restrictive rating was

problematic enough (as a New York Post stunt proved when 12-year-olds

were able to buy tickets).[27] But

even if the gore and sex were absent, what sense might children make out of

watching, desiring or identifying with Johnny Rico? Again using a random sampling of on-line teen chats as an

indicator, it seems that many reacted to eye-candy as they might with other

films: ³This film rocks.² ³Johnny is awesome.² ³Diz is one hot babe.² (Fantastic cinematography!) With Trooper characters as

representatives of a fascist utopia, what will these same viewers think when

confronted with other fascistic principles? Hitler addressed his youth. Heinlein wrote his book as juvenile literature. Is Verhoeven juvenile enough for

today¹s ten-somethings?

not to mention the Disney imprimatur. The film¹s restrictive rating was

problematic enough (as a New York Post stunt proved when 12-year-olds

were able to buy tickets).[27] But

even if the gore and sex were absent, what sense might children make out of

watching, desiring or identifying with Johnny Rico? Again using a random sampling of on-line teen chats as an

indicator, it seems that many reacted to eye-candy as they might with other

films: ³This film rocks.² ³Johnny is awesome.² ³Diz is one hot babe.² (Fantastic cinematography!) With Trooper characters as

representatives of a fascist utopia, what will these same viewers think when

confronted with other fascistic principles? Hitler addressed his youth. Heinlein wrote his book as juvenile literature. Is Verhoeven juvenile enough for

today¹s ten-somethings?

Finally,

we might ask if Starship Troopers lends aid and comfort to the

enemy. If Robin Wood is correct

that Rocky and Indiana Jones would be at home in a fascist pop culture, how

much more pleasure would this starship fantasy yield with its shiny patriots

exterminating an alien enemy? As

with Hitler loving Fritz Lang¹s Metropolis for all the wrong reasons,

intentions would cease to matter.

³Nobody making films today alludes to

Riefenstahl.² -- Susan Sontag

When

Verhoeven, frustrated by criticism, yells to the press ³I am not a

fascist! I¹m a Democrat!²[28] I

believe him. He is right. Starship Troopers is not a

fascist film. Nonetheless, a film

sprung from a democratic spirit shouldn¹t be so difficult to separate from a

fascist one. Verhoeven need not

become a propagandist in the manner of Goebbels or even Heinlein to speak

clearly. His films¹ portrait of

human societies as ugly, harsh and depraved might be redeemed by just a scrap

of hope, by reference to an alternative. For all their depravity, Robocop and Total

Recall at least center on protagonists searching for their human identity,

fighting against corrupt corporate states. But with no Ronny Cox villain to deride, the Big Bug Picture

lacks a target. Incoherence, not

irony, is the postmodern trait that best demarcates this film. With Starship Troopers the

incoherence becomes nihilistic, leaving the unfortunate residue of

fascist-inspired images to resonate in ways that still matter.

If

there is a way to read this war story in a less distressing way, it stems from

the film¹s own construction of impotence.

Despite all the gun-toting and the firing of 300,000 plus rounds of

ammunition, the disciplined, devoted, clean, lean warriors of the Mobile

Infantry remain no match for the intimidating space insects. An assault rifle might have been a

macho problemsolver for John Rambo, but Johnny Rico proves inferior to the

arachnids below him and the mind-managers above him. As we learn in the final scene, the only hope the Federation

has for beating the bugs is a new breakthrough in telepathic mindreading. Carl, Johnny¹s Goebbels-inspired

friend, has become the officer in charge of psychic research. He has (possibly) remotely controlled the

foot soldier's thoughts with ³psi orders² during the final rescue mission. Able to siphon intelligence from the

captured Brain Bug, the Federation¹s military can now out-think its enemy. Of course mind control -- mass trance

through propaganda and ritual -- is also a fascist weapon par excellence. In this sense the film¹s visual display

shares the calculated effect of Riefenstahl and Speer¹s spectacles of

order. In Triumph of the Will

(as in Riefenstahl¹s Olympia, 1938) the Nazis¹ show of arms matters

little in comparison to their pageant of bodies massed in uniform. Thousands of young German troops are

seen armed with shovels, rather than the guns forbidden by the 1918 disarmament

treaty. Political power grows not

from raw military force, but out of the spectacular and its ability to generate

consent to the imagemaker¹s vision.

Ultimately,

this is why Starship Troopers is not an explicit symptom of some

resurgent militant fascism. It

can¹t happen here because the film does not adequately connect its viewing

public to any real political movement which might be seen as a referent for

Verhoeven¹s mock ³utopia.² As

Stephen Prince aptly puts it in his analysis of Robocop, even if one

concedes that the film provokes a progressive political outrage, the lack of a

tangible organization for kindred social action severely limits the film¹s

efficacy.[29] However, this hardly

makes Starship Troopers a work to be lauded. Diehard supporters might argue that by being so

unremittingly coarse, sadistic and destructive, Verhoeven¹s oeuvre rips the

mask off of Hollywood¹s commercial formula, revealing its truly corrupt

heart. Yet even critics like Fred

Glass, who find progressive politics in Verhoeven¹s dystopian movies, should

ask in the last instance the question Glass does about Total Recall. ³What will the audience remember most

when it leaves the theatre: the

politics. . . or the blood?²[30]

With

Verhoeven¹s work there seems little question that it his gore and blood that

stick. His films certainly problematize

the politics of issues like gun violence, militarism, and corporate corruption,

but we might wish that this imagemaker¹s vision were clearer and more

articulate -- especially when playing with fascism. Rather than resorting to a nihilistic response to the

political present, one might recall the clarity of singer Woody Guthrie. ³This machine kills fascists,² he

scrawled across his guitar.  Paul

Verhoeven and Hollywood in general don¹t have to make the cinematic equivalent

of ³This Land Is Your Land² to signal what position they take on the

possibilities of a fascist utopia.

But neither do they need to produce films as ideologically muddled as Starship

Troopers. Perhaps, as Mamet,

Berman and a host of cultural critics have contended, there is something almost

inherently fascistic and controlling in the this machine of cinema that

³transforms the world into a visual object.² Not all pictures and narratives are endowed with the same

political meanings and historical referents, however. Contemporary filmmakers like Verhoeven, aware of a contested

cinematic past, would do well to consider more carefully which side they arm

for the future.

Paul

Verhoeven and Hollywood in general don¹t have to make the cinematic equivalent

of ³This Land Is Your Land² to signal what position they take on the

possibilities of a fascist utopia.

But neither do they need to produce films as ideologically muddled as Starship

Troopers. Perhaps, as Mamet,

Berman and a host of cultural critics have contended, there is something almost

inherently fascistic and controlling in the this machine of cinema that

³transforms the world into a visual object.² Not all pictures and narratives are endowed with the same

political meanings and historical referents, however. Contemporary filmmakers like Verhoeven, aware of a contested

cinematic past, would do well to consider more carefully which side they arm

for the future.

Notes

1 Michael Wilmington, ³Bug Wars,² Chicago Tribune, November 7, 1997, p. A7. Attention to Starship Troopers was also diminished by the inordinate amount of publicity given to Titanic (James Cameron, 1997), released at the same time. Reviews of the movie were mixed. Despite extensive promotion by Sony/TriStar and Disney the film's box office declined quickly after a strong opening. ST grossed approximately half its production cost in its domestic release and earned roughly the same amount money through its international distribution by Disney's Touchstone.

2 According to screenwriter Ed Neumeier, the fictional Morita (a ³futuristic-looking assault shotgun²) was jokingly named after ³a then-current Sony executive.² Paul M. Sammon, The Making of Starship Troopers (New York: Boulevard Books, 1997): 73.

3 Susan Sontag, "Fascinating

Fascism," in Under the Sign of Saturn (New York: Vintage, 1980), pp. 73-105. Recent studies have made it clear that films produced under

fascism seldom resembled Triumph of the Will, but usually eschewed

explicitly political content.

"Escapist" entertainment -- musicals, comedy, adventure tales,

melodrama and the like -- were the popular forms in Fascist Italy and Hitler¹s

Reich. See James Hay, Popular

Film Culture in Fascist Italy (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987), Marcia Landy, Fascism in

Film: The Italian Commercial

Cinema, 1931-1943 (Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press,

1986), Thomas Elsaesser, ³Hollywood Berlin,² Sight and Sound, January

1998, pp. 14-17.

4 J. Hoberman, ³The Fascist Guns in the West,² American Film March 1986, pp. 42-44. Hoberman cites David Denby's 1985 critique in New York magazine as specifically using the fascist label for Rambo: First Blood, Part II (George Cosmatos, 1985), Red Dawn (John Milius, 1984) and other films of that season. See Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan. New York : Columbia University Press, 1986; Michael Ryan and Douglas Kellner, Camera Politica: The Politics and Ideology of Contemporary Hollywood Film, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988; Susan Jeffords, The Remasculinization of America: Gender and the Vietnam War

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 19890; Stephen Prince, Visions of Empire: .

Political Imagery in Contemporary American Film (New York : Praeger, 1992).

5 The Wonderful, Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl [Die Macht der Bilder: Leni Reifenstahl] (Ray Müller, 1993). In 1998, Riefenstahl was deemed wonderful enough to be invited to Time magazine¹s 75th anniversary party (presumably because of her legacy as an artist) and horrible enough to remain vilified for her role in the Nazi propaganda apparatus.

6 Verhoeven alludes to his own fascination with bodily mutilation as being part of the Dutch tradition of etching and painting. Sammons, 140.

7 Prince, 171-84.

8 Paul Verhoeven's visit to the Radio-TV-Film Program at the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh occurred November 3, 1995.

9 Helmut Krausser, ³Faschismus light im Weltall: Paul Verhoevens Sternenkriegsfilm Starship Troopers is ein frivoles Meisterwerk,² Der Spiegel 5 (1998): 179. Graciously brought to my attention and provided by Nicholas Vaszonyi.

10 The icepick through the victim¹s face, footage of oral sex enacted by Michael Douglas and Sharon Stone, and date-rape violence had to be cut to achieve an R rating. The whole of Showgirls was a sort of calculated set piece. Chiefly promoted as the first major Hollywood NC-17 release, the film was universally panned for dialogue and acting so inane they managed to upstage the film¹s ubiquitous nudity. It was instant camp, but unintentionally so since Verhoeven¹s usual cold, hyper-ironic distance is absent. Fortunately, even the shockmeister demurred from any playfulness at the unfortunate (and virtually unmotivated) gang-rape scene that appears in the final act.

The savage gun violence in his best known films notwithstanding, Verhoeven is definitely a knife man. The image of the castrating blade runs consistently throughout his films. In Turkish Delight the lothario protagonist uses scissors to clip pubic hair swatches from his sexual conquests and saves them in a souvenir book. In The 4th Man the title character has a nightmare in which the femme noir castrates him with a pair of scissors. Verhoeven's first English-language production, Flesh + Blood [a.k.a. The Rose and the Sword] (1985) is a bloody 16th-century swordplay film. Even Showgirls features the teen heroine wielding a switchblade against the man who rapes her roommate. In Starship Troopers, the assault on the Brain Bug is not a gun attack but Carmen slicing off the bug's long brain-sucking appendage with her knife. In basic training, Sgt. Zim demonstrates that a knife is still an effective weapon by skewering an infantryman's hand.

Verhoeven himself comments on the fetish/motif in a promotional interview appended to the video release of Basic Instinct (the director's 'cut'). Some people say Sharon Stone's character's icepick is a Freudian phallic symbol, he says. "I don't think so," but it may be, he admits. If so, "I have repressed it."

11 David Mamet, Writing in Restaurants (New York: Vintage, 1986): 16.

12 Russell A. Berman, ³Written Across Their Faces: Leni Riefenstahl, Ernst Jünger, and Fascist Modernism,² in Modern Culture and Critical Theory: Art, Politics, and the Legacy of the Frankfurt School (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988): 99.

13 Elsaesser, 14.

14 Robin Wood, ³Papering the Cracks: Fantasy and Ideology in the Reagan Era,² in John Belton, ed., Movies and Mass Culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996): 211-13.

15 The only film which Wood identifies as clearly fascist in its politics is Schwarzenegger¹s Conan the Barbarian (John Milius, 1982) with its Wagnerian allusions, celebration of Arnold¹s ³Aryan physique² and Nietzschean text. While Verhoeven cast Schwarzenegger in a more complicated role in Total Recall, a project now in development would have Verhoeven directing the action hero in the historical pageantry of The Crusades.

16

Everett Carl Dolman's ³Military, Democracy, and the State in Robert A.

Heinlein¹s Starship Troopers,² in Donald M. Hassler and Clyde Wilcox,

eds., Political Science Fiction

(Columbia, SC: University of South

Carolina Press, 1997): 196-214,

contains the best discussion of Heinlein's philosophy and debates over its fascistic nature. See also books by Franklin, Panshin, Olander and Greenberg, and Stover (cited on bibliography below). The charge of fascism draws heated defenses from Heinlein enthusiasts, as the on-line discussions about Starship Troopers at the time of the movie¹s release and the book¹s re-issue indicate.

17 Sontag, 91.

18 Sontag, 94.

19 Benjamin Svetkey, ³The Reich Stuff: Nazi References and Fascist Images Creep Among the Bugs in Starship Troopers,¹² Entertainment Weekly, November 21, 1997, pp. 8-9.

20 The Buenos Aires setting is largely ignored, although there is a comic close-up of a framed picture of Evita lying in the rubble after the meteor attack. The film was set to be released about the same time as Madonna's Evita (1997), but held up six months for various marketing reasons.

21 Conforming to the hoary Hollywood formula, the most "ethnic" characters are dispensed with first, Shujimi eaten by a bug, Djana¹d washed out of basic training after her rifle accidentally kills a fellow trainee. The majority of principal trooper roles were played by actors who had appeared on Aaron Spelling TV series ³Beverly Hills 90210² or ³Melrose Place.²

22 Sontag, 86.

23 Stephen Hunter's stinging critique of the movie points this out. His review was by far the most trenchant immediate analysis of the film's fascist core. ³Goosestepping at the Movies,² Washington Post, November 11, 1997, p. D1.

24 Sammon, 138-39.

25 Kent Mitchell, ³Movies Corps Values: Trooper¹ on Reading List,² Atlanta Constitution, November 7, 1997, p. 22.

26 Hunter, D1; Stephen Hunter, ³Ooze and Aahs: Why Disgusting, Slimy Movies are Hard not to Watch,² Wasington Post, December 9, 1997, p. D1; Rita Kempley, ³Starship Troopers,² Wasington Post, November 7, 1997, p. D1; Terry Lawson, ³Starship Troopers¹ Sucks Out Our Brains -- and It Feels Great,² Detroit Free Press November 7, 1997.

27 "Despite 'R' Rating, Kids Sneak into Troopers," Reuters/Variety wire report from America Online, November 1997. Sony executives, apparently trying to justify disappointing sales, sent a letter to exhibitors (citing the New York Post story) advising them to check for moviegoers under seventeen who were supposedly sneaking into Starship Troopers after buying tickets to other films.

28 Sontag, 95; Svetkey, 9. Although Entertainment Weekly used a capital D, one suspects Verhoeven meant small-d democrat, rather than Bill Clinton Democrat. In response to criticism, the Starship Troopers official web site (a facsimile of the Federal Network seen in the movie) added a ³Would you like to know more?² section about the controversy. In mocking tones, the film¹s producers admit to ³propagandistic themes and overtones.² As if to goose up box-office receipts, the display headlines that:

Activists from Save the Bugs¹, Brownpeace¹, and TAG [Terran Actors Guild] are calling for Citizens and Civilians Federation Wide to boycott the film. Director Paul Verhoeven was not available for comment. The Office of the Sky Marshal is reported to have responded to the allegations as pure poppycock.¹

The actual Anti-Defamation League dismissed the film as too ³ludicrous² to take seriously. http://www.spe.sony.com/Pictures/SonyMovies/movies/Starship/ (Accessed 1997-98).

29 Prince, 180.

30 Fred Glass, ³Totally Recalling Arnold: Sex and Violence in the New Bad Future,² Film Quarterly 44 (1990): 7, quoted in Prince, 185.

Selected

Bibliography

Books and secondary essays

Affron, Matthew and Mark Antliff, eds. Fascist Visions: Art and Ideology in France and Italy. Princeton University Press, 1997.

Berman, Russell A. Modern Culture and Critical Theory: Art, Politics, and the Legacy of the

Frankfurt School, University of Wisconsin Press, 1988, especially ³The

Aestheticization of Politics:

Walter Benjamin on Fascism and the Avant-garde,² (pp. 27-41), and³Written Across Their

Faces: Leni Riefenstahl, Ernst

Jünger, and Fascist Modernism,² (pp.

99-117).

Cockburn, Andrew. ³Gun Crazy.² American

Film December 1985, pp. 48-52.

Dalle Vache, Angela. The Body in the Mirror: Shapes of History in Italian Cinema. Princeton University Press, 1991.

Deutschmann, Linda. Triumph of the Will: The Image of the Third Reich. Wakefield, NH:

Longwood Academic, 1991.

Dolman, Everett Carl. ³Military, Democracy, and the State in Robert A. Heinlein¹s Starship

Troopers.² In Donald M. Hassler and Clyde Wilcox, eds., Political Science Fiction

(University of South Carolina Press, 1997): 196-214.

Eco, Umberto.

³Eternal fascism.² Utne

Reader, Novemer-December 1995, pp. 56-60.

Eco, Umberto.

³Ur-fascism.² New York

Review of Books, June 22, 1995, pp.

12-16.

Elsaesser, Thomas. ³Hollywood Berlin.² Sight and Sound, January 1998,

pp. 14-17.

Franklin, H. Bruce. Robert A. Heinlein:

America as Science Fiction.

New York: Oxford University

Press, 1980.

Galkin, A. A.

³Fascism,² in The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, tr. of 3rd ed., (New

York: MacMillan, 1970), pp. 1086-88.

Glass, Fred.

³Totally Recalling Arnold:

Sex and Violence in the New Bad Future.² Film Quarterly 44.1 (Fall 1990): 2-13.

Golomstock, Igor. Totalitarian Art in the Soviet Union, the Third Reich,

Fascist Italy and the People¹s Republic of China, Robert Chandler, tr. New York: IconEditions, 1990.

Hay, James.

Popular Film Culture in Fascist Italy: The Passing of the Rex. Indiana University

Press, 1987.

Heinlein, Robert A. 1959. Starship

Troopers. New York: Ace Books, 1987/1997.

Hewitt, Andrew.

Fascist Modernism:

Aesthetics, Politics, and the Avant-garde. Stanford University Press, 1993.

Hoberman, J.

³The Fascist Guns in the West.²

American Film March 1986, pp. 42-48.

Jeffords, Susan.

The Remasculinization of America: Gender and the Vietnam War. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989.

Landy, Marcia.

Fascism in Film: The

Italian Commercial Cinema, 1931-1943.

Princeton University Press, 1986.

Mamet, David.

Writing in Restaurants.

New York: Vintage, 1986.

Neumeier, Edward. Starship Troopers screenplay. Third draft. Unpublished MS, October 6, 1994.

Olander, Joseph and Martin Greenberg, eds. Robert A. Heinlein. New York: Taelinger, 1978.

Panshin, Alexei.

Heinlein in Dimension: A

Critical Analysis. Chicago:

Advent, 1968.

Prince, Stephen. Visions of Empire: Political Imagery in Contemporary

American Film. New York :

Praeger, 1992.

Ryan, Michael and Douglas Kellner. Camera Politica: The Politics and Ideology of

Contemporary Hollywood Film.

Bloomington: Indiana

University Press, 1988.

Sammon, Paul M.

The Making of Starship Troopers . New

York: Boulevard Books, 1997.

Sarris, Andrew.

³Fascinating Fascism Meets Leering Leftism.² In Politics and Cinema. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978): 107-115.

Sontag, Susan.

³Fascinating Fascism.² In Under the Sign of Saturn (New

York: Vintage, 1980): 73-109.

Stover, Leon.

Robert A. Heinlein.

Boston: Twayne, 1987.

Tyler, Parker.

The Shadow of an Airplane Climbs the Empire State Building: A World Theory of Film. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1972.

Wood, Robin.

³Papering the Cracks:

Fantasy and Ideology in the Reagan Era.² In John Belton, ed., Movies and Mass Culture (New

Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University

Press, 1996): 203-28.

_______ .

Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan. New York : Columbia University Press, 1986.

Periodical Press

Carr, Jay.

³Starship Troopers Save Planet from Infestation of Killer Proportions.² Boston

Globe November 7, 1997, p.

D1.

Clark, Mike.

³Starship Troopers on Beeline to Blockbuster.² USA Today November

7, 1997, p. D2.

Dawidziak, Mark.

³R-rated Stuff Really Remiss in Raucous Sci-fi Romp: Brief Nudity, Ultra-gore Out of Place

in Starship Troopers.¹² Akron Beacon Journal, November 7, 1997. ohio.com

Deitch Rohrer, Trish. ³House of Buggin¹.² Premiere, November 1997, pp. 74-77.

Denby, David.

³Rambo: First blood, Part II.²

New-York June 3,

1985, pp. 72-73.

_______ . ³Starship Troopers.² New York,

November 17, 1997, pp. 72+.

"Despite 'R' Rating, Kids Sneak into

Troopers." Reuters/Variety wire report from America Online, November

1997.

Fine, Marshall. ³Starship Troopers.² November 7,

1997. Gannett News Service, in, Courier-Journal.com.

Frost, Terry.

³Starship Troopers, Dumbship Troopers.² Festivale 1997.

Melbourne, Australia. Februry 4,

1998. www.festivale.com.au.

Geier, Thom.

³R-rated Alien Bugs Your Kid Will Beg to See.² U.S. News and World

Report, November 10, 1997.

Giles, Jeff.

³Starship Troopers.² Newsweek, November 10, 1997, p. 78.

Gliatto, Tom.

³Starship Troopers.² People,

November 17, 1997, p. 21.

Glieberman, Owen. ³Starship Troopers.²

Entertainment Weekly, November 7, 1997.

Grossenberger, Lewis. ³Look, Don¹t Touch.² Mediaweek, November 17, 1997,

p. 42.

Hunter, Stephen.

³Goosestepping at the Movies.² Washington Post, November 11,

1997, p. D1.

_______ .

³Ooze and Aahs: Why

Disgusting, Slimy Movies are Hard not to Watch.² Washington Post,

December 9, 1997, p. D1.

Kemp, Philip.

³Utopia.² Sight and Sound, February 1998, pp. 24-25.

Kempley, Rita.

³Starship Troopers.² Wasington

Post November 7, 1997, p. D1.

Krausser, Helmut. ³Faschismus light im Weltall: Paul Verhoevens Sternenkriegsfilm Starship Troopers is ein

frivoles Meisterwerk.² Der Spiegel 5 (1998): 179.

Lawson, Terry.

³Starship Troopers¹ Sucks Out Our Brains -- and It Feels Great.² Detroit Free Press November 7,

1997.

McCarthy, Todd.

³Starship Trooopers.² Variety, November 3, 1997, pp. 98-99.

Maslin, Janet.

³No Bugs Too Large for This Swat Team.² New York Times, November

7, 1997, p. E14.

Matzer, Marla.

³Marketing Starship Troopers is Storming the Gates of an Industry

Generally More Comfortable with G-rated Movies.² Los Angeles Times, October 30, 1997, p. D8.

Mitchell, Kent.

³Movies Corps Values:

Trooper¹ on Reading List.²

Atlanta Constitution, November 7, 1997, p. 22

Morgenstern, Joe. ³Among the Predators and the Prey.² Wall Street Journal,

November 7, 1997, p. A17.

Nashawaty, Chris. ³Quit Buggin¹ Me.² Entertainment Weekly 405 November

14, 1997, pp. 42-45.

Nichols, Peter M. ³Whistler¹s Mother Wouldn¹t Have Sat Still for This.² New

York Times, November 16, 1997, p.

II, 34.

O¹Donnell, Paul. ³We¹ve Already Seen the Future.² Washington Post,

December 14, 1997, p. C2.

Puig, Claudia.

³Paul Verhoeven Regroups.² Los Angeles Times, November 7, 1997, p. D1.

"Despite 'R' Rating, Kids Sneak into

Troopers." Reuters/Variety wire report from America Online, November 1997

Rainer, Peter.

³Future Shock Troops:

Director Paul Verhoeven Bugs Out in Starship Troopers .² Westworld.com New Times, Inc. Nov. 1997.

Rosenberg, Scott. ³Melrose vs. the Monsters: The Incoherent Film Version of Robert Heinlein¹s Starship

Troopers¹ lacks the courage of the book¹s fascist conclusions.² Salon

November 7, 1997.

Schickel, Richard. ³Starship Troopers.²

Time, November 10, 1997, p.

102.

Strauss, Neil.

³50s Sci-fi Camp Goes High-Tech.² New York Times, November 10, 1997,

p. E1+.

Svetkey, Benjamin. ³The Reich Stuff:

Nazi References and Fascist Images Creep Among the Bugs in Starship

Troopers.¹² Entertainment

Weekly November 21, 1997, pp.

8-9.

Thompson, Gary.

³It¹s Sci-fi Genocide.² Knight-Ridder News Service, November 15,

1997. The [Bergen] Record

Online..

Travers, Peter.

³Starship Troopers.² Rolling

Stone, November 27, 1997:

pp. 113 (4).

³Troopers¹ Romps Amid Mayhem.² MSNBC.com,

Entertainment, November 1997.

Turan, Kenneth. ³Stop Buggin¹ Me!² Los Angeles

Times, November 7, 1997, p.

19.

Wilmington, Michael. ³Bug Wars.² Chicago Tribune, November 7, 1997,

p. A7.