Library and Information Science’s Role in Cultural Diplomacy:

Democracy, Propaganda or

Partnerships Abroad?

by

Dr. John V. Richardson Jr.

UCLA

Professor of Information Studies

3 February 2012

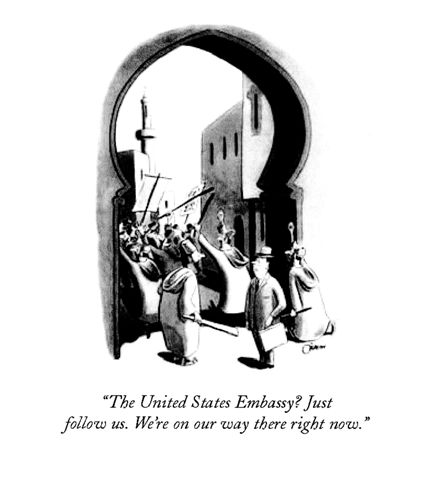

William

O'Brian, New Yorker, 26 April 1958

Definitions

1.

Propaganda (1718): "the spreading of ideas, information, or rumor for

the purpose of helping or injuring an institution, a cause, or a person"

according to the online version of Merriam-Webster’s

Collegiate Dictionary (accessed 29 October 2007)

2.

Diplomacy (1796): “1: the art and practice of conducting negotiations between nations;2 : skill in

handling affairs without arousing hostility,” according to the online version

of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary

(accessed 21 February 2006) and as opposed to the historical practice of

“personal diplomacy” or “the new diplomacy” of the 1920s and 1930s or more

recently “conference diplomacy.”

3.

Cultural Diplomacy (1934): “1: The British Council

created as an arm of British cultural diplomacy and a focus for teaching

English as a foreign language….” according to the OED; 2: “Under the

Vienna Convention, the functions of a diplomatic mission include (1)

representation of the sending state in the host state, which extends beyond the

social and ceremonial, for an envoy is a substitute for his state in that

country, (2) protection within the host state of the interests of the sending

state and its nationals, including their property and shares in firms, (3)

negotiation on behalf of his state with the host state and signing the resultant

agreements when authorized, (4) reporting and gathering information by all

lawful means on conditions and developments in the host country for his

government, and (5) promotion of friendly relations between the two states and

furthering their economic, cultural, and

scientific relations, which includes commercial diplomacy….,” according to

“Modern Diplomacy Practice” in the Encyclopedia Britannica

(accessed 21 February 2006).

4.

Public

Diplomacy

(1965): “Public diplomacy . . . deals with the influence of public

attitudes on the formation and execution of foreign policies. It encompasses

dimensions of international relations beyond traditional diplomacy; the

cultivation by governments of public opinion in other countries; the

interaction of private groups and interests in one country with those of

another; the reporting of foreign affairs and its impact on policy;

communication between those whose job is communication, as between diplomats

and foreign correspondents; and the processes of inter-cultural communications.

..Central to public diplomacy is the transnational flow of information and

ideas." As used in an early

brochure of the Edward R. Murrow Center for Public Diplomacy at the Fletcher

School of Law and Diplomacy at

Quotable Quotes

“Globalization

moves societies into liberal capitalism.” (Henri Dou & Sri Damayanty Manullang, 2004)

“Internationalization

of higher education is both a reaction to, but also, an agent of globalization.”

(Abdullahi, Kajberg, Virkus, 2007)

General Context Readings

Nicolas J. Cull, US Propaganda and ‘Public

Diplomacy' Overseas Since 1945: A History of the United States Information

Agency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005.

Nicholas

Cull, American Propaganda

and Public Diplomacy Overseas Since 1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press,

in press.

Wilson

Dizard, Inventing Public Diplomacy: The Story of the U.S. Information

Agency. Lynne Rienner Publisher, 2004.

Harvey B. Feigenbaum, Globalization and Cultural Diplomacy. Issue Paper on Art, Culture & the

National Agenda. Washington, DC: Center

for Arts and Culture, George Washington University, 2001.

Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash

of Civilizations: Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996,

especially “Preface.”

Henry Kissinger, Does America

Need a Foreign Policy? Toward a Diplomacy

for the 21st Century. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001,

especially chapter 7 “Peace and Justice.”

Henry E. Mattox, The Twilight of Amateur Diplomacy: The

American Foreign Service and Its Senior Officers in the 1890s. Kent, Ohio:

Kent State University Press, 1989.

Geoffrey C. Middlebrook, “The Bureau of Educational and Cultural

Affairs and American Public Diplomacy during the Reagan Years: Purpose, Policy,

Program, and Performance,” PhD Dissertation, University of Hawaii, 1985.

“A recurrent tension in American public diplomacy as conducted by

the United States Information Agency (USIA) is the proper relationship between

the Agency's "twin pillars": informational programs and educational

and cultural programs. The dispute involves issues of incompatibility, as these

two sets of activities differ in modality and purpose. Because of these

disagreements, institutional structures and organizational patterns have been a

constant struggle in American public diplomacy. Concern over the integrity of

USIA's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs was heightened with the

election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency. Observers initially concluded that

the Agency was unduly emphasizing

information at the expense of culture and education, and at the same time

inappropriately politicizing the latter programs. Congress moved to protect the

Bureau, and the result was that it experienced what appeared to be a period of

unprecedented enrichment. Nonetheless, there continued to be talk of separating

the Bureau from the Agency.

This

dissertation examines, describes, and evaluates the purposes, policies,

programs, and performance of the United States Information Agency's Bureau of

Educational and Cultural Affairs during the years 1981 to 1989. More precisely,

it seeks to answer three basic research questions: To what extent and in what

ways was the Bureau enhanced and/or diminished during the period? What were the

essential dynamics at work in this strengthening and/or weakening of the

Bureau? What implications do these changes have regarding the optimum

institutional location for the Bureau? Based on the evidence, the research

conducted herein indicates that: in general the Bureau was enhanced in the

areas of budgets, activities, and stature; these changes were the result of a

productive conflict that occurred between the executive and legislative

branches, at the center of which was the Agency Director, as they negotiated

the definition and direction of the Bureau; USIA is presently and for the

foreseeable future the best organizational home for the Bureau.” (Emphasis added; Author Abstract)

Frank A. Ninkovich, U.S. Information Policy and

Cultural Diplomacy (No. 308). Series editor, Nancy L. Hoepli-Phalon. New York: Foreign Policy Association, 1996.

Frank A. Ninkovich, The Diplomacy

of Ideas: U.S. Foreign Policy and Cultural Relations, 1938-1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Involvement of Library and Information Science

A. Office of War Information (established 1942)

1. Rugen, "Overseas Information Libraries of the US

Government," MSLS Thesis, Western Reserve University, 1950; “they do not

want propaganda”

2. Babin, "Book Selection Policy of

the US Information Libraries," MSLS Thesis, Catholic University, 1951

B.OWI disestablished by Turman (disestablished1946)

1. Office of International Information and Cultural Affairs (OIC)

renamed Office of International Information and Educational Exchange (1947)

C.

US Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 (aka Smith-Mundt Act or PL 80-402)

D.

United States Information Service (established 1953)

1. Foreign policy (Clemens, "The Pivot: The USUS Libraries in

Germany and the US Department of State," MLS Specialization Paper, UCLA,

1982)

2. Collection development (Wenning,

"Books Removed from the USIS Libraries," MA Thesis, Florida State

University, 1956)

i. 82

books removed;

ii. 20

titles by 8 authors said to be “Avowed Communists;” and

iii. 55

titles by 20 authors who refused to testify before Permanent Subcommittee on

Investigations

E.

United States Information Agency (established “to expose the ‘untruths’ of

communism,” 1957)

1. John F. Kennedy, defined the role of USIA to promote

“democracy”

2. Edward R. Morrow, appointed Director (1961)

F.

USIA Advisory Commission (William F. Buckley; “On the Right” and “Firing Line”)

G. International Communication Agency (too easily confused with CIA)

under President Jimmy Carter

H.

Merged into the United States Department of State (Fall 1999) due to Jesse

Helms and Madeleine Albright agreement

Gary E. Kraske, Missionaries of

the Book: The American Library Profession

and the Origins of United States Cultural

Diplomacy. Westport, CT:

Greenwood Press, 1985.

Having visited American Centers and American Corners in Eritrea

(Asmara and Keren), Russia (Moscow, St.

Petersburg, Vladivostok, and Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk), Uganda, and Zambia, it was

clear to me in 2002 that the Department of State needed to consider an “opening

day” collection of core reference materials consisting of books, journals, and

magazines which would support American studies in these countries. They have

since done so.

Updated: 3 February 2012

R;tw