The works in this exhibit are all later versions or publications of titles, authors, or documents that are represented in the Rouse Medieval Manuscript collection. The exhibit content was created by students in a History of the Book seminar in Winter 2014 in the Information Studies Department at UCLA.

Exhibit Home

1. An exact collection of all remonstrances,...

3. Divi Avrelii Avgvstini Hippon. Episcopi...

4. Horae in laudem beatiss[ima] Virginis secu[n]dum....

5. Hore in laudem beatissime Virg[inis] Marie...

6. Les memoires, contenans le discours de plusieurs...

7. Modus Bene Viuendi (Modus Bene Vivendi)

8. Psalteriu[m] v[ir]ginis sanctissime [secundum]...

9. Q. Asco. Pediani In Ciceronis orationes...

10. Quaestiones super XII libros Metaphysicae...

11. Stimulus diuini amoris Sancti Bonauenturae

12. Varii sermoni de Santo Agostino...

13. Varii sermoni di Santo Agostino

Title Breuiarium Cartusiensium

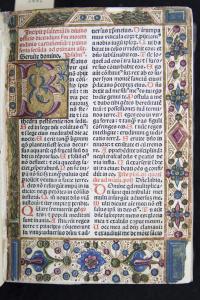

Brief description The Breuiarium Cartusiensium contains a beautiful illuminated page and was printed by Andree Thoresani de Asula based in Venice. He was the father-in-law of Aldus Manutius, a renowned printer, and carried on Manutius’ printing business after his death in 1515. Beyond the artistic merit, the book represents an early form of printing in both black and red ink. The book itself demonstrates the importance of the Catholic Church to the early printing industry. As both a commissioner of books and author of texts, the Catholic Church was one of the main sources of work for early printers and undoubtedly helped the industry to flourish. The book also points to at least one group who was literate in Latin in Medieval Europe and who had access to high quality books. Catholic leadership such as bishops and priests used breviaries like this one for daily services to recite prayers and hymns, among other liturgical practices. The small size of the book indicates that it was carried with an individual and designed for personal use. This breviary also points to an interesting development in divergent texts. Until Pope Pius V in the late 1500s, each monastic community could have its own breviary and “every bishop had full power to regulate the breviary of his own diocese.” Thus local variations like the Carthusian Breviary were unique to that community or diocese. The Roman Breviary is now the most widely-used version, showing that breviaries continue to be important and relevant texts within the Catholic Church. Today there are even breviary apps available for smart phones. Note: According to an Italian website the printer’s mark found in the breviary is that of Andrea Torreggiani, but there seems to be no other evidence to support this claim. It is possible that the printer mark is Andrea Torresani or Torresano, but the mark most often attributed to him differs from the one found in this breviary.

Physical description Two sections of about 20 pages are added photocopies. The text is primarily in two colors (black and red). Larger letters indicating new sections are in blue. Some sections appear to be handwritten in brown ink including the last three pages.

Content description The text is a Carthusian breviary. There is an extensive entry on Wikisource of the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica entry for the term “breviary”. The description focuses on the Roman breviary, but explains that a breviary “contains the offices for the canonical hours, i.e. the daily service of the Roman Catholic Church.” This breviary is specific to the Carthusian order which was founded in 1084 by Saint Bruno of Cologne. The name of the order originates from the Chartreuse Valley in modern day France.[1] It is difficult to tell when the text itself was written since it was roughly adapted from the Bible, and several different editions and types, such as Roman and Dominican breviaries, have evolved. This text was developed from the Bible and from other pre-existing texts related to liturgical practices of the Catholic Church such as the psalter. It served as a guide for bishops and priests to lead daily services. They could use it to recite prayers and hymns, and it contained a liturgical calendar for services. According to the above-mentioned Encyclopædia Britannica entry, in early Christianity, several books were needed to conduct a mass. Therefore, “To overcome the inconvenience of using such a library the Breviary came into existence and use.”[1] Catholic leadership such as bishops and priests. The more indirect audience would be the congregation who listened to the prayers and hymns from the book recited by the priest. The title suggests that it was used by and created for the Carthusian order and used during the liturgy and in preparation for daily service. The Bible and other liturgical texts such as the psalter have been fairly influential in the field of theology in that it served as a reference for priests during daily services. In fact breviaries are used today and there are even breviary apps for smart phones. [1] Wikisource. “1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Breviary.” Accessed February 16, 2014. http://en.wikisource.org/w/index.php?title=1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Breviary&oldid=4192361 [1] The Carthusian Order. “The Origin.” Accessed February 23, 2014. http://www.chartreux.org/en/origin.php

Contributor: Hannah Mosier

Contribution date: Winter 2014

Full title: Breuiarium Cartusiensium

Date 1491

Location Venetijs (Venice,Italy)

Dimensions 3in w, 5in h, 2in d

Technologies of production Letterpress Printing

Additional information There are 25 copies at various institutions but they are 11 different editions of the book. According to WorldCat only the University of Cambridge has the same edition. There is a Carthusian Breviary available through Google Books, but it is a different and much later edition. Several institutions have the book on microform.

ConditionSome wear but in generally good condition. One page has a burn mark and some pages appear to have wax stains. Handwritten notes on almost every page.