When industrialization appeared in Western culture, it brought changes to every arena of activity, including book production. The cultural conditions for production and consumption brought new readerships, printing techniques, and concepts of art to bear upon the forms of the codex. Mass production of printed matter was fostered by the creation of papermaking machines, presses powered by steam and then electricity, and gradual automation of all aspects of the printing process.

Illustrational techniques proliferated expanding the vocabulary of relief printing and hand-painting. Experiments in photographic production and reproduction, color printing, and other innovations extended the range of imagery readily available in book forms. Binding machinery enabled automation collating, gluing, sewing, and casing—all functions performed earlier by hand bookbinders hired to cater to their patrons’ individual taste and style in their private collections. In short, book production exploded in the amount and range of volumes produced and marketed. Publishing houses, usually family imprints at first, became big businesses.

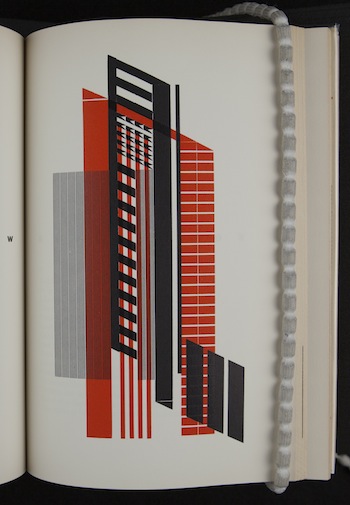

In the fine arts, the trend away from strict patronage support and towards free markets in speculative goods created an autonomy of artist and work that existed within new patterns of consumption. Fine press, private press, the arts and crafts movement, and the avant-garde all contributed their own counterpoint to the mainstream production of mass market works. Innovation and conservatism flourished at either end of the aesthetic scale, and the art of the book, fed by aesthetic concerns raised in successive movements of creative and critical thought, embodied the precepts of these waves of intellectual and imaginative life. But books also had their own champions, and the book as a form of art in its own right was also proclaimed in treatises and tracts outlining aesthetic guidelines and beliefs.

This exhibit focuses on a few outstanding examples of book art from the beginning of the 19th century through to the middle of the 20th. An argument could be made, based on changes in fine art and literature, that Modernism is on the wane in the period following the second World War, and that Postmodernism, with its self-consciousness about the end of history, originality, and artistic autonomy, creates a different framework for production than had existed in the slightly more than a hundred and fifty years earlier. By the 1960s, a new form of artistic expression in the book format appeared under the rubric “artists’ books,” with much debate, critical proclamation, and many innovations. These are part of conceptual, minimal, and pop art movements which may be considered the final throes of modernism or the full-on start to the postmodern period. Book production by artists of all kinds continues to thrive, however, and works that draw on all of the many styles and conceptions of books, from illuminated manuscripts to lavish, modest, or experimental printed and digital pieces, continue to demonstrate the viability of the dialogue between artists and books in the extended (post)modern period. Many current, ongoing, styles and conceptions of the book as a work of art have earlier roots in the period covered by this exhibit. What is clearly evident in the books from the early 19th century onward is that attention to the material and conceptual aspects of book production made the codex into a work of art in a manner consonant with other modern aesthetic objects. Of course, many exquisite, highly aesthetic, and original works of art in the book format have existed for as long as books and manuscripts have been produced. The uniqueness of the modern period resides in the way these works existed in the context of industrialization and mass production.