The complaint, and the consolation; or, Night thoughts

1. The complaint, and the consolation; or, Night thoughts

2. The Fables of Æesop, and others / With designs on wood, by Thomas Bewick

5. News from nowhere: or, An epoch of rest, being some chapters from Utopian romance

6. The nature of Gothic, a chapter of the stones of Venice

7. Daphnis and Chloe: a most sweet abd pleasant pastoral romance for young ladies

8. The Sphinx

10. Credo

14. Bible.Old Testament. Song of Solomon.

16. Kem byt’? / V. Mai︠a︡kovskiĭ ; ris. N. Shifrin.

17. The ghost in the underblows

19. Bateau ivre

UCLA Call Number: ** PR3782 .N56 1797

The complaint, and the consolation; or, Night thoughts

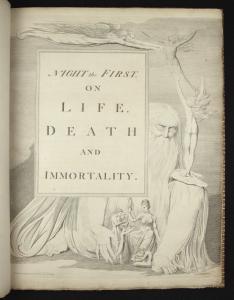

According to the Explanation of the Engravings, this illustration depicts Death in the form of an old man, sweeping away a family with one hand, and with the other offering their spirits up to heaven. It showcases the incredible skill and detail of Blake’s engraving as well as his ability to envision Young’s often allegorical text. Note too that the plate barely fits on the page.

The complaint, and the consolation; or, Night thoughts

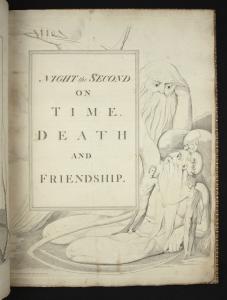

The image depicts the salient elements of Young’s Second Night. It shows Time personified, endeavoring to avert the arrow of death from two friends. It underscores the theme of mortality, with which Night Thoughts deals extensively.

The complaint, and the consolation; or, Night thoughts

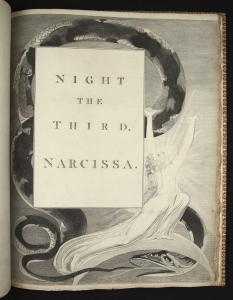

This image depicts the frontispiece to the third night of Young's text. This is among the darkest and most elaborate of Blake’s Night Thoughts engravings. According the explanation included in this copy, this image depicts a female standing on the world, having surmounted its obstacles, being admitted to eternity, as represented by the Ouroboros, the serpent eating its own tail. It is notable that the symbol of eternity isn’t quite formed – the snake’s tail is not quite in its mouth.

The complaint, and the consolation; or, Night thoughts

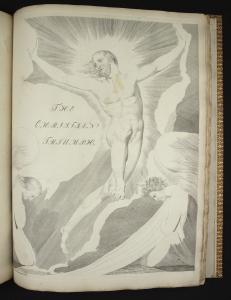

The image represents the fourth night of Young's text and features the text, “The Christian Triumph,” with the image of Christ, nude, arms outstretched, ascending into heaven while an angel kneels in reverence. The explanation in this copy describes this illustration as depicting the resurrection of our savior, typical of all his servants from the grave. It also underscores the Christian faith of both Edward Young and William Blake.

Contributor: Sean Gates

Full title

Creator: Young, Edward

Publisher: Richard Edwards

Publication Place: London

Date of Publication: 1797

Dimensions 45 cm

Physical Description:

This exquisite copy of The Complaint and the Consolation, or Night Thoughtsfrom1797 features the first four “Nights” of Young’s poem, illustrated with 43 copperplate engravings by William Blake. Bound in beautiful gold’tooled red morocco leather [?], this sumptuous edition received little public attention at the time of its publication, save some criticism of Blake's radical designs. Richard Edwards went out of business from publishing this book, and Blake, who received no more than 45 pounds for his contribution, avoided commercial ventures as a means of support thereafter. [SG]

The work is bound in red morocco leather[?], just as the first copies were (Bentley, 2001, 166). The cover has an outer border of three gilded lines, inside of which is an embossed border. In the center, three more simple gilded lines frame an extravagant border of gold tooling featuring an elaborate pattern. Three more gold lines frame a final border of embossing at the very center.

The spine features 5 raised bands. Between the 2nd and 3rd band down is the title, Night Thoughts, and below it, separated by a small horizontal line, the author, “Young,” all in gilt letters. At the tail of the spine it reads “1797,” also in gilt letters.

The UCLA catalog has incorrect information in its notes and physical description. To save time, it was most likely copied it from another institution, most likely the Huntington Library. The UCLA copy is larger than 42 cm and is uncolored, not “hand–colored, possibly by Blake himself,” like the Huntington Library’s copy. This copy is uncut (Blake Archive, Huntington Copy). Its leaves measure 42.5 X 32.5 cm. The volume itself is approximately 44 cm tall.

The first and last blank leaves are laid paper, as suggested by its ribbed texture and subtle grid–like appearance. They bear the watermarks of Abbey Mill in Greenfield, UK. The watermark reads “Abbey Mill” with “Greenfield” below, both in old–fashioned Gothic lettering, with a large crown graphic above. The mill dates back to the 1770s, and was known for making high quality writing and ledger paper. The endsheets at the beginning and end feature green, yellow, blue, and pink marbling. The marbling type appears to be either “french swirl” or “placard,” or perhaps a blend of the two (Middleton, 36). A box, not original, houses the volume, and is composed of wood, lined with red leather, and decorated with marbling that is similar to the endsheets.

High quality wove paper is the primary substrate of the work. The paper was made by J. Whatman in 1794. Blake used Whatman paper for other projects as well, such as Nebuchadnezzar and Vala: The Four Zoas (Bentley, 2001, 159, 198). Only some pages of the 1797 copies feature Whatman’s watermark, which reads oddly enough, “J. Whatman,” and beneath it “1794.” In this copy, the watermark can be found on pages iii, vii, 19, 23, 31, 35, 61, 77, 81, and 93.

The binding is sewn, with a brown and white striped headband.

The work features a total of 43 black and white engravings. A starred line indicates the subject of the illustration. On many pages, one can see the impression left by the plate against the paper. Bentley notes that “the bottoms of many of the plates have been trimmed (in the nine copies examined), occasionally removing the dates,” perhaps accounting for the missing dates on some of the plates. (Bentley, 1964, 167).

Most of the plates were published on June 27, 1796. The inscription “Pubd. June 27th. 1796, by R. Edwards, No. 142 New Bond Street” appears on pages 1, 4, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15–17, 19, 23–27, 31, 33, 35, 49, and 70. The engravings on pages 37, 43, 55, 57, 63, 73, 75, 86, 87, 90, 92, and 95 are not dated. Page 40 is dated “Jan. 4, 1797,” and page 46 is labeled “Jan. 1, 1797.” Pages 65, 72, 80, 88, and 93 are June 1, 1797, and pages 41 and 54 are March 22, 1797 (Bentley, 1964, 167).

The pages are enormous in this sumptuous folio. The engravings surround the text, mostly in the bottom and outer margins.

Blake used a monogram in some of his engravings for Night Thoughts that he used in no other commercial engravings. It consists of his initials joined above by a semicircle inside of which is written “inv & sc.” This monogram is found on pages 7, 8, 12, 15, 16, 19, 23-27, 31, 33, 35, 37, 40, 41, 43, 46, 49, 54, 55, 57, 63, 65, 70, 72, 75, 80, 86, 87, 90, 92, 93, and 95.

Two distinct typefaces are used in the work, one for the introductory and explanatory material, and another for Young’s actual text. Edwards’ enthusiasm for this project stems in part from then–recent developments in English typefaces and bookmaking. Both are Roman typefaces which are wide–set, with vertical stress, and straight, nearly horizontal line serifs (Perfect, 13).

This copy includes both Richard Edward’s “Advertisement” at the beginning, and an “Explanation of the Engravings” at the end, likely written by Fuseli or Richard Edwards. (Keynes, 54). It is certain that Blake did not write it. The preface is attributed by Blake’s friend Alexander Gilchrist to Fuseli, but some scholars believe it far more likely that Richard Edwards wrote it himself (Keynes, 54).

Provenance:

The inside cover bears a bookplate signifying this was a gift of Miss Margaret Gage. Margaret M. Gage was a friend of playwright and poet Charles Rann Kennedy. She was editor of World Within: A Collection of Sonnets by Charles Rann Kennedy, released in 1956, and a resident of Pacific Palisades. Between 1959 and 1982 she donated the Charles Rann Kennedy papers to the UCLA library. At some point in that span of time, she must also have gifted Night Thoughts.

Condition:

This copy is in remarkably good condition, being nearly 220 years old. There is however slight foxing throughout, some water stains near the margins, and an occasional smudge and stain. Foxing occurs most notably on blank leaves and pages 5, 7, 9, 12, 13, 17, 86, and 87. Stains appear throughout the text – little black marks, resembling burns or careless pen marks. Stains appear most noticeably on pages 11, 14, 15, 31, and 59. On pages 92, 93, 94, 95, and 96 the same dark mark appears in the same place, suggesting ink bled through, or possible pest infestation. Smudges may be related to foxing or may simply result from centuries of dirt and dust. The most noticeable smudges are on pages 3, 23, 24, 51, 53. Water stains occur in the margins on pages 31, 53, 74, and on the last blank leaves. The leather cover with embossing and gold tooling is in remarkably good shape, having only minor scratches on front and back, suggesting it is a later binding, perhaps from the early 20th century. The box with which the text comes is also in amazingly good shape, were one to assume it to be original. More likely, both binding and box, whose marbling nearly match, were produced much later than 1795, closer to the early to mid 20th century. The leaves of this copy are uncut, unlike the copy held by the Huntington Library (Blakearchive, Huntington Copy).

Additional Info:

The original idea for the project may have belonged to Henry Fuseli, a painter and friend of Blake and James Edwards, brothers of Richard Edwards, the publisher (Bentley, 2001, 164). For years Blake had dealt with James Edwards, son of the famous William Edwards of Halifax, a very prominent bookbinder and seller. By 1791 Richard Edwards had also established himself in the London booktrade as a producer of ephemera – mostly Church and King pamphlets and a small range of books, often with elegant bindings. Most of his publications were small–scale and lacking in originality. Inspired by the strides made in English typography, book design, and binding in the last three decades, and spurred by productions like Boydell’s Milton and rival Charles De Coetlogon’s own 1793 illustrated Night Thoughts, Richard Edwards undertook to produce his own deluxe edition (Bentley, 2001, 165). Edwards had also recently acquired a set of first and early editions of Night Thoughts, the pages of which were used as centerpieces around which Blake produced his watercolors. Such an ambitious project with such an unknown publisher and an artist known for eccentricity and extravagance made the project subject to criticism. Edwards advertised the book poorly, sent out no copy for review, and no review was printed (Bentley, 2001, 172). While Blake was still engraving, Edwards was preparing to go out of business. A banking crash near the time of publication heavily impacted both potential buyers and Richard Edwards himself. He wound up paying Blake only 45 pounds for his 2 years of work, and he may have even paid Blake with copies of his own book. (Bentley, 1963, 5) (Bentley, 2001, 172). The failure of this project soured Blake on commercial ventures and led him to seek patronage in the person of Thomas Butts.

Interpretation:

This work represents the creative genius of not just one, but two of England’s greatest artists. Night Thoughts is arguably Edward Young’s greatest work, and the engravings were one of the biggest projects Blake ever undertook.

Young’s 1745 poem is an introspective, pre–romantic examination of mortality, morality, nature, God, and self. It was for over a century one of the most influential, praised, and well–known poems in the English language (Young, ix). The publisher's “Advertisement” recognizes it as an “English classick,” comparable to the productions of Shakespeare and Milton. During the Methodist and Evangelical revivals of the 18th century and early 19th century, Night Thoughts was read alongside the Bible and standard devotional works (Young, ix). In addition, Night Thoughts participates in a tradition of philosophical, blank verse poetry, linking Milton’s Paradise Lost to Wordsworth’s The Prelude or The Excursion (Young, 3). With its praise of nature and reliance on “what spontaneously arose in the Author’s Mind,” Young’s poem anticipates the work of romantic poets more than 50 years in the future (Young, 35). Such aesthetic similarities may also explain the revival of interest in 1795 that led to the production of this fine, illustrated folio edition. Indeed publisher Richard Edwards said when he selected Night Thoughts, he wished to “make the arts subservient to the purposes of religion” (Bentley, 76, 2004).

Night Thoughts remains very inspiring. The often elevated diction of 18th century verse does not obscure Young’s grand ideas or deprive the reader of sharing in Young’s more ecstatic moments. Because of its timeless themes and prose–like readability,Night Thoughts remains a very accessible and powerful instance of 18th century inspirational poetry.

William Blake’s contribution elevates this work to a new level. His beautiful and idiosyncratic wood engravings depict the symbolic universe of Young’s poem. 43 engravings in all represent some of Blake’s finest visual art and constitute a good 20% of his total commercial engraving work (Bentley, 1964, 5). They appeared in 1797 and made little public impression except to “startle the pious” (Bentley, 1964, 4). Some ridiculed his designs calling them “the conceits of a drunken fellow or a madman,” (Bentley, 2001, 172). Even Hazlitt said he “saw no merit in the designs” (173). But some were able to see past the novelty and strangeness of Blake’s engravings, like novelist Edward Bulwar Lytton, whose praise still rings true as it reflects another time: “I saw a few days ago, a copy of the “Night Thoughts,” which he had illustrated in a manner at once so grotesque, so sublime––now by so literal an interpretation, now by so vague and disconnected a train of invention, that the whole makes one of the most astonishing and curious productions which ever balanced between the conception of genius and the ravings of positive insanity.” (Bentley, 2001, 175).

Blake’s illustrations hardly strike the modern viewer as especially scandalous, but in 1797, his portrayal of nude bodies so close to verses about divine grace caused a minor uproar. It seems however that Blake was simply ahead of his time, stylistically. The long, graceful, flowing lines with which he depicts female hair and angelic beings resemble the work of Aubrey Beardsley and later Art Nouveau. Blake’s Night Thoughts engravings continue to be appealing – for their amazing detail, their creative design and composition, their high subjects, and Blake’s ingenuity in visually representing Young’s poem.

As this work represents a collaboration between a dead poet and a living visual artist, it might be interpreted as an early example of livres d’artiste.

Text Content Description:

Young’s poem is a didactic and meditative exploration of “man’s mortality in the context of divine judgment” (Young, 13). Written in blank verse, the poem describes the speaker’s musings on death over the course of nine nights, or chapters. Topics include time, friendship, love, fear, God, and infinitude. The poem is remarkable for its praise of nature. Boldly exclaiming “Nature is Christian” (Young, IV,704), Young’s speaker does not believe in a separate transcendent God, or that nature is fallen. Rather, Night Thoughts presents God as a power immanent in nature, who expresses himself through a universe that is endowed with significance (Young, 5). The poem vacillates between the ecstatic and the melancholy, between the triumph of reason and the incomprehensible power of God.

The poem often veers into a passionate lamenting of man’s limitations. The voice is always personal and individual, as signaled by its tangential progression and frequent self–reflexivity. Here, as throughout, Young, like Shakespeare, asks, &dlquo;What is a man?”:

Helpless immortal! insect infinite! A worm! a god!–I tremble at myself, And in myself am lost! At home a stranger, Thought wanders up and down, surprised, aghast, And wondering at her own: how reason reels! O what a miracle to man is man, Triumphantly distress’d! what joy, what dread! Alternately transported and alarm’d! What can preserve my life, or what destroy? An angel’s arm can’t snatch me from the grave; Legions of angels can’t confine me there. (Young, I, 80–90)."

The poem copes with the hard truths of human existence. True to Enlightenment thinking, Night Thoughts emphasizes Reason as the great cure for man’s condition; however Nature and Christ are also integral to Young’s argument.

Night Thoughts contains the oft–quoted line: “Procrastination is the thief of Time” (Young, I, 393).

Only the first four “Nights” are included in this Richard Edwards publication of Night Thoughts. Indeed, Blake’s 43 engravings represent only a fraction of the 200 envisioned. His copperplate engravings represent Young’s frequent personifications, allegorical figures, and biblical references. They are splendidly designed and imbued with Blake’s unique vision. Starred lines In Young’s text indicate the subject of the illustration. The book ends with “Night The Fourth,&rddquo; “The Christian triumph,” in which Jesus Christ is displayed ascending with arms outstretched.

At a time in which the graphic–novel is becoming a well–accepted genre, its interesting to see a graphic–poem. Truly, Blake’s illustrations make Young’s text come to life, replete with mythic significance and imaginative intensity.

Contributor: Sean L. Gates