The Sphinx

1. The complaint, and the consolation; or, Night thoughts

2. The Fables of Æesop, and others / With designs on wood, by Thomas Bewick

5. News from nowhere: or, An epoch of rest, being some chapters from Utopian romance

6. The nature of Gothic, a chapter of the stones of Venice

7. Daphnis and Chloe: a most sweet abd pleasant pastoral romance for young ladies

8. The Sphinx

10. Credo

14. Bible.Old Testament. Song of Solomon.

16. Kem byt’? / V. Mai︠a︡kovskiĭ ; ris. N. Shifrin.

17. The ghost in the underblows

19. Bateau ivre

UCLA Call Number: Clark PR5820.S751 1894

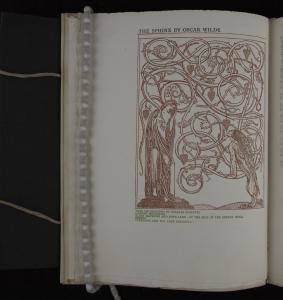

The Sphinx

This image shows the title page, the majority of which is an illustration of a figure, which looks similar to the Virgin Mary, who holds onto grape vines that span the width and height of the illustration. As has been said of Rickett’s illustrations, the vines are clearly grapes, making them botanically identifiable, but perhaps more interesting is the figure of the Sphinx herself, causally reaching for a bundle of grapes with her mouth. The juxtaposition of the two female figures is interesting–the modest, slim, feminine Mary who looks, in this moment, not so modest as she watches the muscular, somewhat androgynous Sphinx take what she desires, and seems almost aroused by the assertiveness and sexual prowess of the animalistic figure before her. This proves to make those characteristics of the Sphinx that much more apparent.

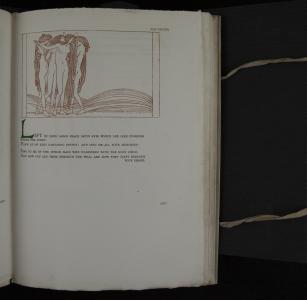

The Sphinx

Interior page of The Sphinx showing the features of the page design: woodblock drawing, running head, and text set in small caps up close to the image and very tight on the page. The effect is unusual, and the delicacy of the type’s spiky serifs matches the line of Ricketts’s drawing style perfectly.

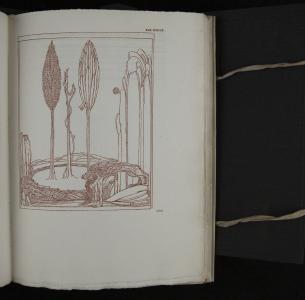

The Sphinx

This illustration reveals the Sphinx’s sexual nature as she positions herself, stretching out immodestly across the bottom quarter of the page. Her hair falls wildly as she reaches her hands into the water. Her muscles are prominent, her figure able–bodied and strong. Her animalistic qualities are front and center and are almost the most densely detailed of all the shapes and figures in the illustration. Another figure, a man perhaps, is quietly watching her from the other side of the river–much less detailed, a vertical shape that blends into the stones and trees, this figure is much less assertive, but is interested or attracted by the Sphinx. This speaks to the Nouvelle woman that Wilde and Ricketts are emancipating with their imagery.

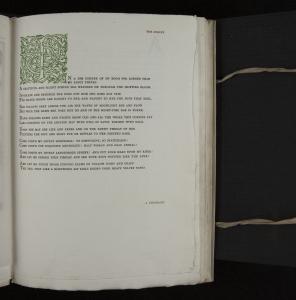

The Sphinx

This image shows Page 1 of The Sphinx, the beginning of the actual poem. It begins with an illuminated initial, the “I” of the first couplet, which only drops one line while reaching a greater height than the other text. It contains eight couplets total and a catchword in the bottom right hand corner.

The Sphinx

The cover is an interesting piece of art as it reveals Rickett’s Greek vase design influences and use of Egyptian iconography. The Sphinx is bound in vellum with gold inlaid illustrations on the front and back covers, as well on the inside corners of the vellum folds. Imprinted on each of these corners is a small, gilt Eye of Horus. The binding includes two ribbons of end tape.

-->

Creator: Wilde, Oscar

Publisher The Ballantyne Press (publisher); Vale Press (printer)

Publication Place: London

Date of Publication: 1894

Location

Dimensions: 23cm

Physical Description:

The Sphinx is an exquisite piece of work. Its vellum cover is smooth to the touch, but stiff, unlike the suppleness of leather one might expect. The gold leaf imprints on the cover still glitter when touched by light. The paper is of high quality and feels textured. Several blank fly pages at the beginning and end of the book give it the feel of uncovering a “treasure” that is buried inside. The end tapes, which are off–white ribbons, now aged and faded, hang about six inches over the end of each cover. The book itself is fairly light and easy to handle; although it is in great condition, without any noticeable foxing or deterioration in the binding, it somehow still could be called fragile.

Somewhat flat and smallish, it is an easy read from cover to cover in one sitting. A rather short book with only 35 pages, and with each page containing between two and nine couplets, the book is a fast read. The type is highly readable and clear when compared with the heavier, Gothic–influenced types of the Kelmscott books. One reason for this is that the type is in all capitals, a move Ricketts says he made to “mark” his text with “surviving classical traits” (“Pall Mall” 184–5). In person, the colors of the ink are striking, and it becomes easy to imagine the excitement of the reader, especially as this was one of the first books to appear with three different colored inks. The green ink is a grass green, pleasant to the eye but bold and primary in nature. The rust colored ink is a muted, blood red with almost light brown. Although muted, the rust is still a strong color and humbles the green ink with hints of organic earth and dirt. The black ink, which is used primarily for the body of the text, is clear and consistent, but not strong, overpowering, or heavy.

Provenance:

In William Clark’s 1936 inventory list, he takes an account of each of the items in his library. In this list, several copies of The Sphinx are noted, with the first listing being a 1894 1st edition on large paper. Next to this listing is a price of $143. This entry allows us to assume this edition was part of the Clark collection as of 1936. It is still to be determined when the edition was purchased for this amount. One clue could be a handwritten inscription on the inside of the cover of this edition, which reads: ϕTRM. Rosenbach 2/21/24 And. Sale 1820 #11095. This could possibly indicate that the purchase was made on February 21, 1924, as this is prior to the 1936 inventory date, but that merely speculation.

Additional Info:

Unlike other Vale Press books, Rickett’s illustrations in The Sphinx were wood engravings causing some to argue, including Ricketts himself, that it was not a real Vale Press book. Daphnis and Chloe, like other Vale books, was created using woodcuts for its illustrations (Frankel 91). Another one of the first editions (out of the 200 copies that were made) sold at a Sotheby’s auction on July 10, 2013 or $4097. Its description read: “decorated title–page and other illustrations by Charles Ricketts, printed in black, light red and green, original pictorial vellum gilt by Charles Ricketts, uncut, covers slightly bowed and very slightly marked.”

Interpretation:

Oscar Wilde commissioned Charles Ricketts to illustrate his poem The Sphinx after first coming across Rickett’s and his partner Charles Shannon’s literary/artistic journal The Dial in 1889:

The first number [of The Dial] so impressed Oscar Wilde that he came to The Vale to meet the two and is said to have begged them not to bring out a second number, as 'all perfect things should be unique’ […] Wilde commissioned Ricketts to design his books (with the sole exception of Salome) which were published by Osgood McIlvaine & Co. […] several of them like […] Wilde’s own The Sphinx (1894) are now regarded as among the finest books of the period.” (Cave 114).

The Vale Press officially ran from 1896–1904, and published between forty–six and forty–eight different works. Notable besides The Sphinx (1894) are Daphnis and Chloe (1893), Hero and Leander (1890), The Kingis Quair (1903) and the complete works of Shakespeare as one work in thirty–three volumes. Situated between two artistic moments–the Arts and Crafts movement of fine bookmaking, which was a reaction against the shoddy bookmaking that came out of the Industrial Period that preceded it, and the burgeoning sensual and exoticist design of Art Nouveau–the goal of the Vale Press was both to revive medieval bookmaking sensibilities, but more importantly, to stretch the limits of design and the medium. Ricketts, like William Morris, Emery Walker, T.J. Cobden–Sanderson, and others, sought to make the finest books possible, with careful consideration of every detail, from paper, to binding, to ink, to illustration. Yet, Ricketts&srquo; books were different than Morris’ Kelmscott books or Cobden–Sanderson’s Doves Press works. Vale books tended to be more “quiet and modest” than those from some of the other fine presses. Vale floral patterns are more botanically correct than Kelmscott’s, and Vale books feature a more “delicate” and “precise” line (Franklin 86).

Rickett’s books, according to Sir Francis Meynell, were each “conceived freshly in terms of its literary materials, the design sometimes chiming with, sometimes counterpointing the qualities of the subject.” Ricketts utilized a “sensitive” line and “sinuous view of drapery or anatomy” –and took his influence from Aubrey Beardsley and the style of art nouveau” (Franklin 86). The same year that The Sphinx is published, Beardsley, a nineteen–year–old illustrator, launched the publication of The Yellow Book (1894), preceded by the illustrated version of an edition of Oscar Wilde’s play Salome (1893). Beardsley’s style borrowed from the eastern, Japanese aesthetic made popular by such artists as James Whistler (1834–1903), due in part to Japan’s recent trade agreement with Britain (forced upon Japan after American warships arrived in Tokyo Bay in 1854). Influenced by the ideas of Charles Baudelaire, Whistler’s work espoused a new aesthetic ideal that included images of nature, sweeping, flowing lines and curved angles, and, most importantly, the nouvelle woman, who was sensual and exotic. Umberto Eco describes the Jugendstil (or German Art Nouveau) woman as “erotically emancipated, sensual woman who rejected corsets and loved cosmetics: from the Beauty of book decorations and posters, Art Nouveau moved on to the beauty of the body” (Eco 369).

In the later half of the century, Beardsley was instrumental in promoting this “body” aesthetic, including most famously, his illustrations of Salome. It has been noted that his “sheer sexual suggestiveness was never equaled by any of his followers”; “with monstrous and sinister–grotesque subjects,” he was able to achieve work of powerful sexual suggestiveness unlike anyone else of his time (Drucker 176, Taylor 119). While the Sphinx herself is described by Wilde’s text as having “large black satin eyes– which are like cushions where one sinks!” with lust, with having a penchant for multiple lovers and for calling them by their “secret names,” the women in Rickett’s Sphinx do not quite achieve Beardsley’s level of “suggestivity” or “monstrosity.” Elements of the nouvelle woman do appear to influence his illustrations, however. Ricketts’s imagery often mirrors these descriptions, fulfilling Eco’s depiction of the nouvelle women who were created by a “Beauty of line,” which did not diminish the “physical, sensual dimension”; “and the female body in particular lends itself to envelopment in soft line and asymmetrical curves that allow it to sink into a kind of voluptuous vortex” (Eco, 369). In contrast, Meynell remarks of T.J. Cobden–Sanderson’s books–a contemporary of Ricketts and another fine press operator: “They are lovely, impeccable, taut and silky like young muscles in play; but they are in series a little automatic, a little boring: typographical Tiller girls,” referring to the popular 1900s chorus dancers who formed a line of dancers who matched not only in dress and choreography, but even in weight and height (Taylor 84). (1)

According to Eco, the “Narcissistic” beauty of the Art Nouveau moment: “project[ed] itself onto the external object and appropriate[ed] it, enveloping it with its lines.” Thus, the concept of “line” for Ricketts (as well as for Beardsley and others) was a transformative factor in their overall design principles. It was through “line” that Ricketts was able to transgress the book object, transforming it into a space, rather than a flat, two–dimensional plane. Book designer and artist Johanna Drucker explains Rickett’s theory of design, which aligns nicely with Eco’s account:

Ricketts considered the book an entire, integral work from cover and spine through the page layout and sequence. Rather than revive historical imagery, Ricketts devised a motif of closets and interior cabinetry as an order and structure within which to make the improbable idea of a conversation with a sphinx believable. […] In a daring move, Rickett’s left significant portions of the page unfilled to provide volume and architecture of the text and images. (Drucker 177)

Compared with the book design of the Industrial period and the heavily medievalist revivalism present in Morris’ Kelmscott books, Vale Press books, in particular The Sphinx, were a daring leap in transforming book design.

References:

Allingham, Phillip V. “The Technologies of Nineteenth–Century Illustration: Woodblock Engraving, Steel Engraving, and Other Processes.” The Victorian Web. Accessed: 06 Oct 2014. Web.

Cave, Roderick. The Private Press. New York: R.R. Bowker Company, 1983. Print.

Drucker, Johanna and Emily McVarish.Graphic Design Guide: A Critical History.

New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009. Print.

Enniss, Stephen. “Printing Yesterday and Today.” Educator Programs. Web.

http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/educator/modules/gutenberg/books/printing/

Frankel, Nicholas, The Sphinx, critical edition; Rice University Press, 2009.

[CHECK]

Franklin, Colin. “Vale, Eragny and a Link with the Aesthetic Movement.” The Private Presses. Hants, UK: Scolar Press, 1991. pp.81–105. Print.

Moran, James. Printing Presses: History and Development form the Fifteeth Century to Modern Times. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1973. Print.

Orcutt, William Dana. Master Makers of the Book. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1929. Print.

Primorac, Yelena. “Illustrating Wilde: An examination of Aubrey Beardsley’s Interpretation of Salome.“ The Victorian Web. Accessed: 06 Oct 2014. Web.

R. Hoe & Company: Catalogue of Printing Presses and Printers’ Materials. Ed. Bidwell, John. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc.,1980. Print.

Sex and Sensibility: The Allure of Art Nouveau – British cities. BBC Documentary. 2012. Accessed: 22 Oct 2014. Web.

Taylor, John Russell. “Art Nouveau in the Nineties.” The Art Nouveau Book in Britain. London: Methuen &Co., 1966. Print.

The Pall Mall Magazine. Ed. Lord Frederic Hamilton. Vol. 22 September to December 1900. London, W.C. Oxford Union Society. Web.

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiller_Girls

Text Content Description:

What might strike a reader when encountering The Sphinx is that, more than any other book they might have come across, the text and illustrations of this text interact almost symbiotically to produce a highly visual image. Part of this is due to the potent vision of each of the artists who made this text. Frankel describes how “The Sphinx abounds not in real things but in 'ideal objects,’ which are convoked and dissolved in a moment, according to poetic needs…[The] word forms a poetic object created by the author” (Frankel quoting Borges 84). So while Wilde is making “word objects” for the reader that are produced through the breakdown and re-–reation of ideals, the illustrations follow “Rickett’s own precept that 'illustration ought to give the book an accompaniment of gesture and decoration, perhaps also an added element of visual poetry’ ” (Taylor 84). Thus, the poetic language and engraved illustrations both work to produce what Rickett says is his ultimate vision for this text: “the imagining of some charmed moment and place” where the artist could steal the best from the ancients and transcend their limits.

Wilde’s poem, The Sphinx, details the ruminations of the narrator on the imagined life of the Egyptian monument, the Sphinx, which is a huge statue that is part cat, part woman. The text plays out a series of possible “encounters” and “affairs” of the Sphinx, some of which rely upon Egyptian historical figures and others that allude to Egyptian mythology. The figure of the Sphinx becomes the aforementioned nouvelle woman–full of unabashed desire and sensuality. Her figure creeps in and out of the frames of each page and Wilde’s poetry continuously imagines her exploits, expanding upon the free and limitless sexuality of her character. She is seductive and unashamed, quiet and lurking in the corners, yet huge and statuesque, unable to fully hide in the corners of the poem. Wilde describes her features, her “tawny throat,” “soft and silky fur,” “ripples to her pointed ears,” “curving claws of yellow ivory,” a “tail that like a monstrous Asp coils round your heavy velvet paws!” each as animalistic, threatening, yet somehow softly feminine. Rickett’s drawings reveal her slinking in from all sides of the page, crouching, waiting to pounce on food, object, and person, or to lead some unsuspecting person to her lair. In some drawings she is more animal, in others she is more woman, but always with some animalistic feature.

Rickett’s accompanying illustrations reveal a myriad of influences, some traditional and some more 'exotic' and 'idiosyncratic.' Taylor describes how “Ricketts shared with Whistler and with all the major figures of art nouveau a profound admiration for Japanese styles and conventions,” as well as an interest in Greek vase design, “Celtic intricacies of intertwining shapes,” decorative borders, and a commercial design sensibility, all of which contributed a rare heterogeneous group of influences and “eccentric learning” to the formation of “one man’s style” (Taylor 78–9). This is shown in the figures on the cover and throughout, who, although they represent Egyptian mythological characters, are reminiscent of classical Greek figures depicted as they would typically appear on a Grecian urn.

Contributor: Kristin Cornelius Way