Bateau ivre.

1. The complaint, and the consolation; or, Night thoughts

2. The Fables of Æesop, and others / With designs on wood, by Thomas Bewick

5. News from nowhere: or, An epoch of rest, being some chapters from Utopian romance

6. The nature of Gothic, a chapter of the stones of Venice

7. Daphnis and Chloe: a most sweet abd pleasant pastoral romance for young ladies

8. The Sphinx

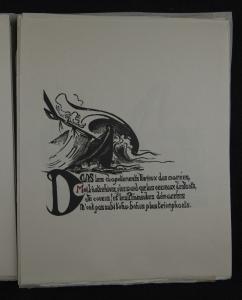

10. Credo

14. Bible.Old Testament. Song of Solomon.

16. Kem byt’? / V. Mai︠a︡kovskiĭ ; ris. N. Shifrin.

17. The ghost in the underblows

19. Bateau ivre

UCLA Call Number: Rimbaud Coll. B3 (Collection 1597)

Bateau ivre

Bateau ivre

Bateau ivre

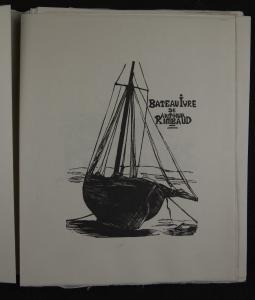

In this photo of the title page we see an image of a ship as well as the title and the author of the poem. The boat appears to be sitting on land and leaning to the right. The bottom of the boat is very dark and has a sense of weight, conveyed by the almost complete blackness with a couple delicate lines of white which show the edge of the ship. The rigging of the ship is stretched across the page and creates a sense of tension. In the top right corner there is text which reads: “Bateau ivre de Arthur Rimbaud.” In the background there is a skyline and what looks like rolling hills loosely indicated with hatch marks. It is interesting to note the humility of the artist as indicated by the striking absence of her own name outside of the colophon. The image shows Nozal’s use of the woodcut to illustrate the themes of Rimbaud’s poem. Her natural style is harmonious and strong, it does not seek to compete with Rimbaud’s text but complements it. The image also shows an example of Nozal’s incorporation of text and illustration as well as her singular typeface which combines elements of modern and Expressionist art with elements of Gothic and incunabula from the Middle Ages.

Bateau ivre

Full title

Creator: Rimbaud, Arthur

Publisher: Julie Jacques Nozal

Publication Place: A Saint-Briac [France]

Date of Publication: 1949

Dimensions: 26 cm. x 22 cm

Physical Description:

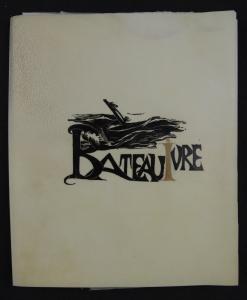

Bateau ivre consists of 47 bifolium, including 42 illustrations. The entire work was created, designed and printed by the artist Julie–Jacques Nozal from woodcuts which she refers to in the colophon as “incunables tabellaires.” Distinctive features include hand–colored illustrations, illuminated capitals, and the use of wood engraving in the style of incunabula. The vellum cover is a beautiful warm, light yellow color with a rich, thick feeling and texture. The cover consists of a folded sheet of vellum. The vellum enclosure has a rich, black woodcut of the words “Bateau ivre” and an image of a wave printed on the cover in ink. The “lower–case i” in the cover title has also been hand–colored in gold paint. Upon touching the cover one is immediately presented with a sense of reverence for such a finely made object. The hand of the artist can be felt throughout in the lines of the woodcut. The paper is unbound and folded in bifolium. The paper is relatively smooth and lightweight, but also fine. It is reminiscent of a Japanese or mulberry paper in that it has a lightness and extremely fine quality.Bateau ivre is printed on Auvergne paper. The paper is not entirely opaque. Often the bow of a ship or a wave will show through onto the verso of a sheet. This is particularly fitting for the subject matter of the poem which tells the story of a ship’s wild travels across a fantastic ocean. There are sheets of tissue interleaved between illustrations, however there has also been some bleedthrough from the oily ink. There are 47 unbound leaves, broken down into bifolium, which are occasionally also separated by a loose sheet. The woodcut illustrations and text are mostly printed in black ink with complements in red, yellow and green.

Provenance:

Bateau ivre is currently held in Special Collections at the Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles. This book is in the Rimbaud Book Collection – collection number 1597, box 2. The bookplate on the pastedown inside the front cover reads: “Donated to the UCLA library by Giles Healey.” The Rimbaud Book Collection consists of five boxes of books. There is no further information regarding the donation of this collection to the UCLA Library. Likewise, there is no donor file for Giles Healey. In the catalog entry for the Rimbaud Book Collection there is a note that indicates “there is an unpublished finding aid for this collection.” This finding aid consists of three sheets of paper which each have one paragraph listing the contents of the boxes; it does not contain any further information.

Condition:

Good condition, no damage or wear. Some bleedthrough from ink onto verso of printed pages, despite protective tissue.

Additional Info:

Bateau ivre is unbound. Additional books in the Rimbaud book collection held in the UCLA Library Special Collections can be found by searching for “Rimbaud Book Collection” in the library catalog. A description of Bateau ivre and its reception can also be found in the “Friends of Rimbaud newsletter,” 1949, record number: 3783280.

Interpretation:

Julie–Jacques Nozal’s Bateau ivre is a singular and magnificent work. This beautiful example of modern wood engraving consists of over forty–two illuminated stanzas plus illustrations of Arthur Rimbaud’s most famous poem “Le Bateau Ivre.” Completed in 1949, when Nozal was sixty–nine years old, Bateau ivre falls outside of her pre–war oeuvre which was distinctly Catholic. Her previous works included Evangile selon Saint Luc (the gospel according to Luke) in 1934, Le jardin de la Vierge (The Garden of the Virgin) completed in 1939, and illustrations for Paillard’s Lumière éternelle (Eternal Light) of 1944. It is an ironic testament to the importance and impact of Rimbaud’s poem that a devoutly Catholic artist completed an illustrated edition of this most secular work which the boy Rimbaud, at age 16, mailed to his soon to be gay lover, Paul Verlaine, just three months after its creation. It is also possible that the impact of World War II had a drastic affect on Nozal’s life and changed the focus of her work. Nozal created this work on the coast of France where her family home “Les Emaux” is still located in the small village of Saint Briac outside of St. Malo. The town of Saint Briac was famous for its royal inhabitants including Marie of Romania and Grand Duchess Kyrill of Russia who were both acquaintances of Nozal. St. Malo was also famous as the birthplace of the writer and historian Chateaubriand, whose Cymodocea Nozalillustrated the previous year. Nozal’s usual work was informed both by her Catholicism and by her artistic and aristocratic lineage. Nozal’s father, the famous enamelist Paul Grandhomme, used Nozal as a model for his busts of Christ. She grew up in an environment of extreme wealth, privilege and patronage of the arts. Nozal led a life characterized by ease and devotion to her craft. Bateau ivre demonstrates a singularity of mind and clarity of practice and form. Despite the impact of yet another World War during her lifetime, four years later Nozal was able to produce Bateau ivre, an astonishing work that could be interpreted as memorializing her loss during the War. St. Malo, which was held under siege by the Germans, was almost completely destroyed by fire. In an interview from 1948, one year before finishing her work on Bateau ivre, Nozal revealed that she was “devastated because she had lost her 4,000 volume library in the firebombing.” [Footnote 1]

In an issue of the Montreal Photo–Journal, from 1948, the author refers to Nozal as “The only woman who makes incunabula,” that is, early printing as it existed prior to 1500. [Footnote 2] The Photo–Journal article points to the fact that Nozal’s practice was characterized by “anachronism and a dedication to the craft of handmade wood engraving.” [Footnote 3] From a technical perspective Nozal employed methods that were in use during the Middle Ages. “Block–books” is the form that Nozal’s style emulates with the incorporation of text and image cut into a single block of wood. The block–book form was originally used for illustrated Bibles and Devotionals, a genre that would be consistent with most of Nozal’s other thematic production. Block–books began to appear in Europe around 1450, but were later replaced by movable–type at the end of the 15th Century. Bateau ivre features pages where text and image are cut into the same block, from which the page is then printed. One difference is that, compared to most block–books, Nozal reserves a significant amount of white space surrounding the text and image, which is centered in the page with about 7cm of white space at the top and bottom. Nozal’s use of white space around the illustrations is a modern idea of page composition as opposed to a “whole page concept,” which would be congruent with the mood of 14th–century authenticity she is attempting to conjure.

As discussed previously, in her Bateau ivre, Nozal seamlessly combines text and image into one work that is produced using the same method of wood engraving. The text is not a separate form in the Bateau ivre, but also functions as an additional sort of illustration. The style of the text appears to be a hybridized Beaux–Arts and Gothic mixture. Throughout, there are references to the Middle Ages and there are incunabula with fabulous, illuminated capitals in the Bateau ivre. An overall sense of naivete and directness in consonance with the youthful production of Arthur Rimbaud at sixteen pervades the work. Le Bateau Ivre or The Drunken Boat, is the 100–line poem that swept across the world of literature like a tidal wave when it appeared in 1871. As indicated by Rimbaud’s title, the voice is that of the “boat itself gradually sinking,” which helped to launch a further move away from Romanticism towards the Symbolism of the fin–de–siecle poets in France.

The use of woodcut, or xylography, while versatile, can also dictate style. In Nozal’s work, this is most evident in the hatch marks and the form of the letters which have a physical and a geometrical natural presence. There is much in Bateau ivre that could be compared with the Modern Art movements, such as Cubism and the Fauves who broke down the picture plane and moved away from classical representation towards abstraction. Her use of the woodcut is reminiscent of the German Expressionists, who, beginning in the early 1900’s, also adopted the woodcut as a more “natural” and “pure” means of production. While Nozal’s work harkens back to Early Europe, she appears to have skipped the Renaissance completely. In the middle of the Twentieth Century, Nozal found herself emulating an artform which was practiced centuries before by artists who also shared her devotion to the Church and handcrafted Book Arts. In her adaptation of an Early European Gothic style, Nozal is not without precedent. William Morris’s Kelmscott Press also looked to the Middle Ages for an aesthetic that was less tainted by the modern evils of industrialization, however with very different results. Where Nozal’s hand can be felt in every line, Morris’s fine press work and “book beautiful” concept yielded a much different form of “Art in the book.” Nozal’s work does not seek to reproduce the Middle Ages, but she clearly draws inspiration from this period even as she traces her own trajectory with a singular hand, and uniquely recognizable style.

1. Lucette, Robert. “Julie–Jacques Nozal Est La Seule Femme Qui Fasse De L’incunable.” Montreal Photo–Journal, October 21, 1948, Lettres Et Arts sec. 45–6 2. Lucette, Robert. Ibid, 45. 3. Lucette, Robert. Ibid, 45.

Text Content Description:

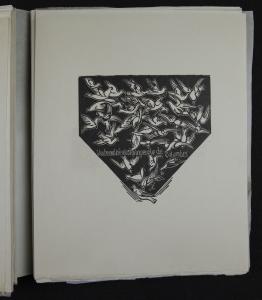

The content of this work is the poem, The Drunken Boat (Le Bateau Ivre), written by Arthur Rimbaud in 1871. The poem is written in alexandrine (12 syllable) quatrains (sets of four lines) with an a/b/a/b rhyme scheme. In the poem, Rimbaud describes the journey of a ship as it floats without any passengers. It slowly fills with water and sinks below the waves. For example, the eighth stanza reads:

“I have come to know the skies splitting with lightnings, and the waterspouts And the breakers and currents; I know the evening, And Dawn rising up like a flock of doves, And sometimes I have seen what men have imagined they saw!”

The poem is written from the perspective of the sinking boat. The boat witnesses strange and fantastic visions which were heavily influenced by Rimbaud’s reading of Jules Verne’s breakthrough novel Twenty–Thousand Leagues Below the Sea. Written at age 16, Le Bateau Ivre was destined to become Rimbaud’s most beloved work in his native France.

Contributor: Ilana Goldszer