Walking in the footsteps of their predecessors in Antiquity, medieval physicians and scientists in Byzantium, the West, and the Arabic World compiled manuals on venoms and poisons. They usually divided the matter into two parts: venomous animals on the one hand and poisons on the other. Each of these two fields was defined by the way lethal substances came into contact with the human body: by inoculation through a bite or a sting for venoms, by oral absorption or cutaneous contact for poisons. Following the classical Greek usage, these two fields were respectively called Thêriaka (a term based on the Greek word thêr, alluding to a wild and dangerous animal) and Alexipharmaka (a term of uncertain origin and meaning, often considered as referring to counter-poisons). Whereas ancient knowledge was mostly devoted to the prevention and treatment of all cases of envenomation and poisoning, the medieval medical literature expanded the field by opening it onto mythological tales, fantastic accounts, popular imagination, and other practices.

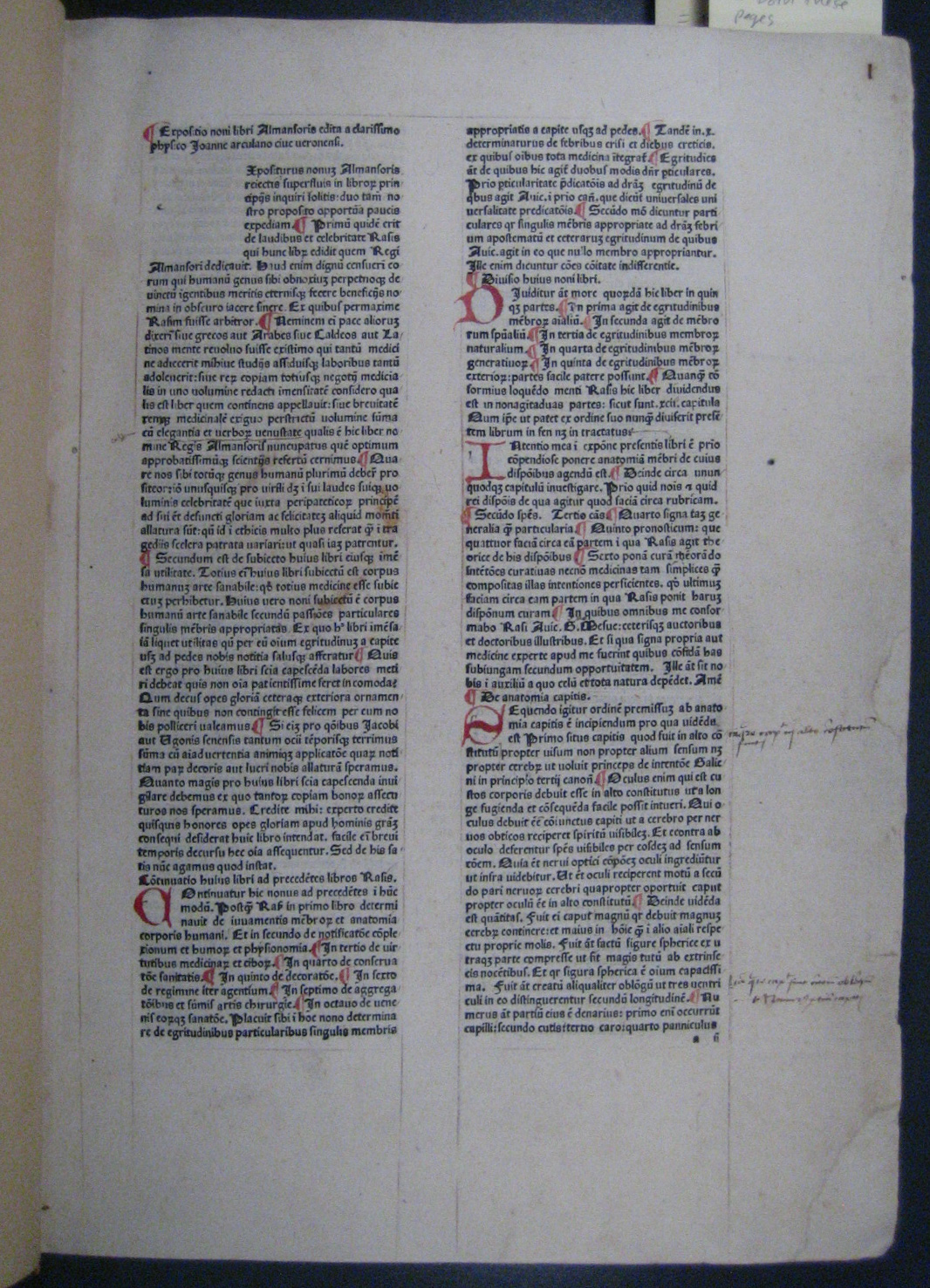

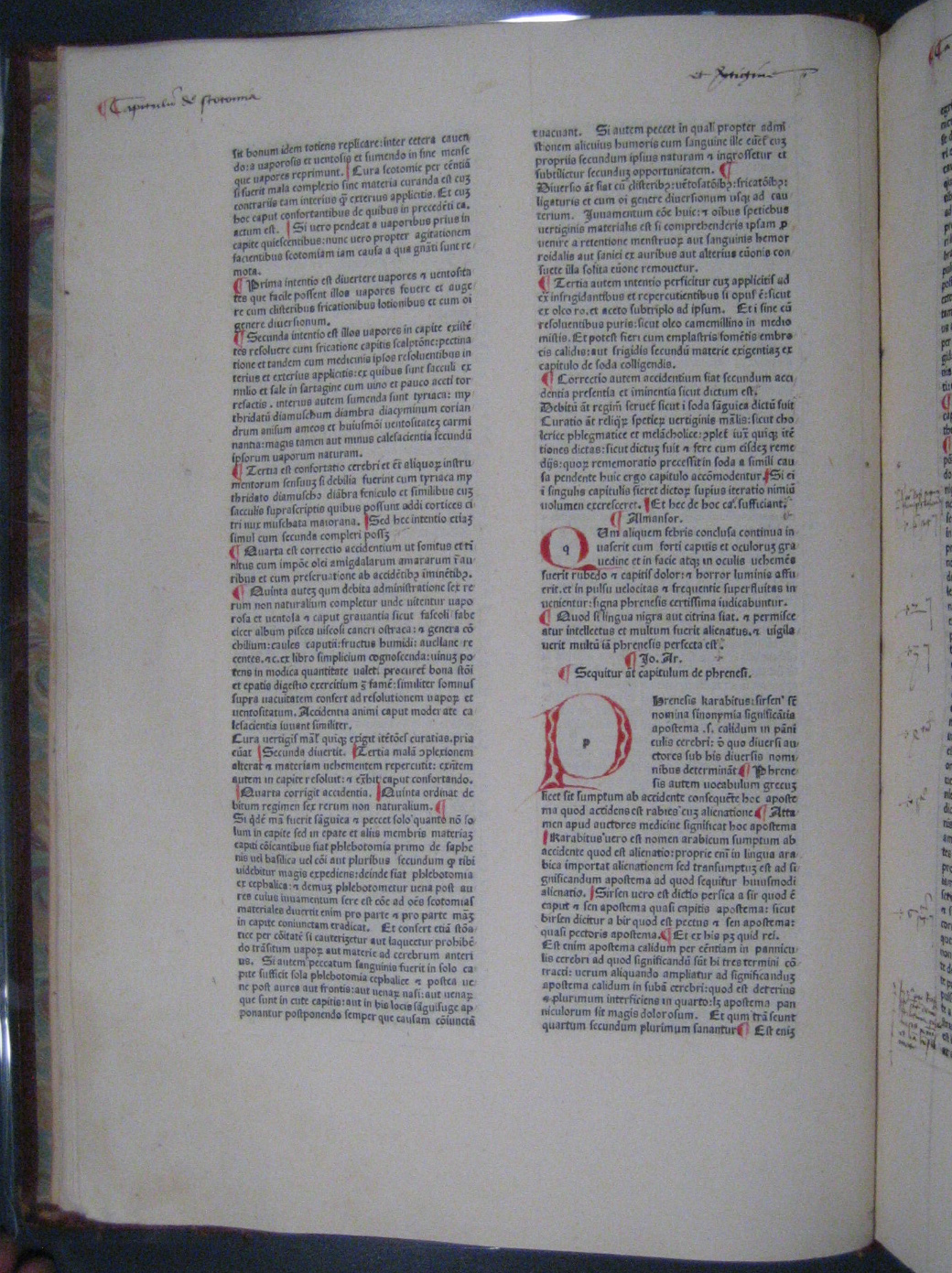

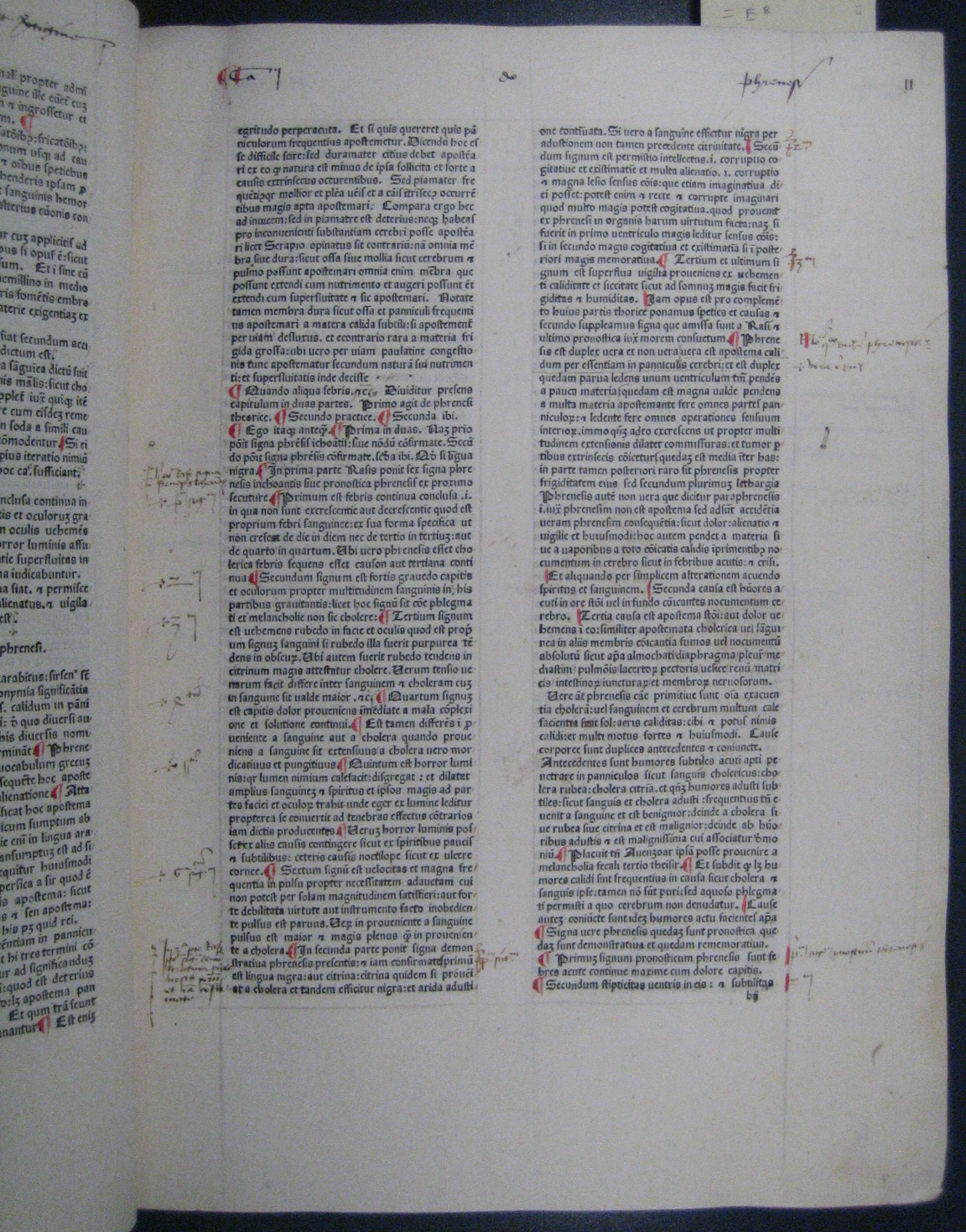

II + 208 + IV ff., 406 x 290 , a5-b5, c4-d4, e3, f4-i4, j5-k5, l3, m5, n4, A4-M4, N3-O3 (first folio of first quire is missing). Padua, Maufer, ca. 1480.

Latin. Text in two columns. Guide lines (ruling) made by printer similar to those used in manuscripts shows early printing technique transitioning from manuscript to print. Rotunda. Many handwritten annotations in the margins.

The work is the Latin translation of a medical encyclopedia by Razi in which diseases are ordered from head to toe according to the principle a capita ad calcem.

UCLA Louise M. Darling Bio-medical Library, Special Collections, Vault, Oversize: WZ 230 M892L 1480.

Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariyya’Al, known in the West as Rhazes, (865-925), was an Islamic physician trained in Galenic Greek medicine. He was born near Tehran and approached medicine as a philosophical study, basing his treatises off of medical texts in Greek, Sanskrit, Syriac, and Arabic. His contributions to the creation of pharmacy are particularly important. Notable works include a description establishing the differences between measles and smallpox, alchemy, as well as discussions on philosophy and religion.

Michael E. Mamura, “Razi, abu Bakr Muhammad Ibn Zakariya Al - (Rhazes),” in Joseph R. Strayer (ed.). Dictionary of the Middle Ages. New York: Charles Scribner’s and Sons, 1988, vol. 10, pp. 267-268.

Hinrich Biesterfeld, “Razi, Abu Bakr Muhammad Ibn Zakariyya’Al,” in Noretta Koertge (ed.). New Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Detroit, Il: Charles Scribner’s and sons, 2008, vol. 6, pp. 211-215.

[JFC]

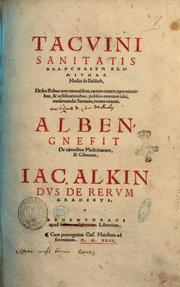

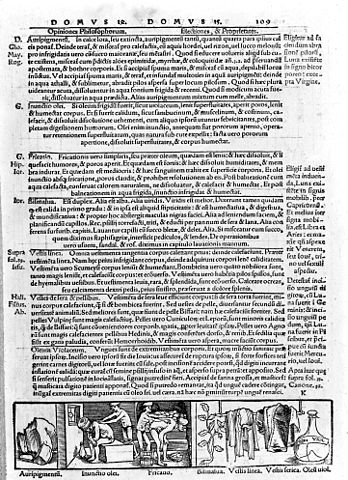

I + 84 + I ff., 320 x 210 mm, A3-M3, N2-P2, Strasbourg, Iohannes Schottus, 1531.

Latin. Text on the full page on the recto of the folios with facing tables on the verso of the previous folio. Roman with smaller marginal type. Two-color printing on the title page. Some ornamental initials. Small woodblocks (hand-colored) on the recto at the bottom of the text, representing the materia medica analyzed on the page.

UCLA copy contains two other works in the same binding, Alben Gnefit de uirtutibus Medicinarum & Ciborum, and Iacalkin Dvs De Rervm gradibvs.

WZ 240 I13t 1531

ibn-Butlan (d. 1066), sometimes known as Elluchasem Elimithar in the West, is best remembered for his work on diet entitled in Arabic Taqwin as-sihhah. This title was transliterated as Tacuinum by medieval translator and was used for works on diet, regimen, lifestyle. The most remarkable characteristic of the work is its employment of tables to present information. ibn-Butlan wrote other medical treatises which focused mainly on remedies, and philosophy. He famously opposed many ancient techniques and instead encouraged a deep respect for ancient medicine while being open to new and better knowledge.

[JFC]

The Tractatus has been published together with the Conciliator of Pietro (on which see 2.2). The following is the description of the complete volume.

V (originally a quaternion of which 3 folios have been cut) + 708 + X ff., 425 x 290 mm, a – g5, h4, i-B5, C-D6, E-L5, M6, N4. Mantua, Lodovichus de Gonzaga Marchione, 1472.

Latin. Text in 2 columns in roman. Blank spaces left for rubricated, hand-drawn initials, for rubricated capital C’s to mark the beginnings of new sentences, and for the occasional hand-drawn diagram.

UCLA Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library Special Collections, Vault, Oversize: **WZ230 A117c 1472

While he is important as an early translator of Galen’s work from Greek to Latin, Pietro d’Abano (c.1257–1316), is most well known for his book Conciliator differentiarum philosophorum et praecipue medicorum (“Concialator of the Differences of the Philosophers and Especially the Physicians”). Completed after 1310, this work was an attempt to reconcile some of the conflicts between Galen’s medical teachings, and Aristotle’s physiological and philosophical teachings. It is influenced by Pietro’s Aristotelian education in Paris, where he went to university around 1300, and was extremely popular, being used by universities up to the early modern period. Pietro d’Abano returned to his home of Padua around 1306 to become a teacher of medicine, philosophy, and astrology at the university. While his connection to Averroistic theories is now disputed, here he was suspected of heresy by ecclesiastical authorities because of, for instance, his attempt to interpret the birth of Christ as non-miraculous. Though he was cleared of these charges during his lifetime, 40 years after his death in 1316, his writings were found to be heretical and thus his body was exhumed and burned.

Faye Marie Getz, “Pietro d’Abano”, in Chistopher Kleinhenz (ed.). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Abingdon, Routledge 2003, vol. 2, p. 897

“Abano, Pietro D’”, in Charles Coulston Gillespie (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1980, vol. 1, pp. 4–5.

[JM]

Contribution date: February 2016