According to a traditional historical narrative, the Middle Ages came after the division of the Roman Empire, the foundation of Constantinople in 330 and the fall of the Western Empire in 476. The world that emerged from these transformations—to which the so-called invasions and the emergence of the Arabic Empire should be added—is often seen as a Latin-speaking one, closed on itself, and static through the centuries. Such a narrative is increasingly transformed by ongoing historical inquiries which reveal a very different image of the medieval world, which went through repeated transformations, was interconnected and multilingual, and was also open to different philosophical and scientific orientations. Besides trade, travels, politics, and military expeditions, translation was an important vehicle for exchanges between the different worlds around the Mediterranean, from Greek into Latin as early as the sixth century CE, from Arabic into Latin from the eleventh century, and, later, from Greek directly into Latin. Multiplicity of contributions was not without risks: an international language made of borrowing from all the languages in contact developed, and different interpretations of science and theories circulated, resulting in occasional conflicts.

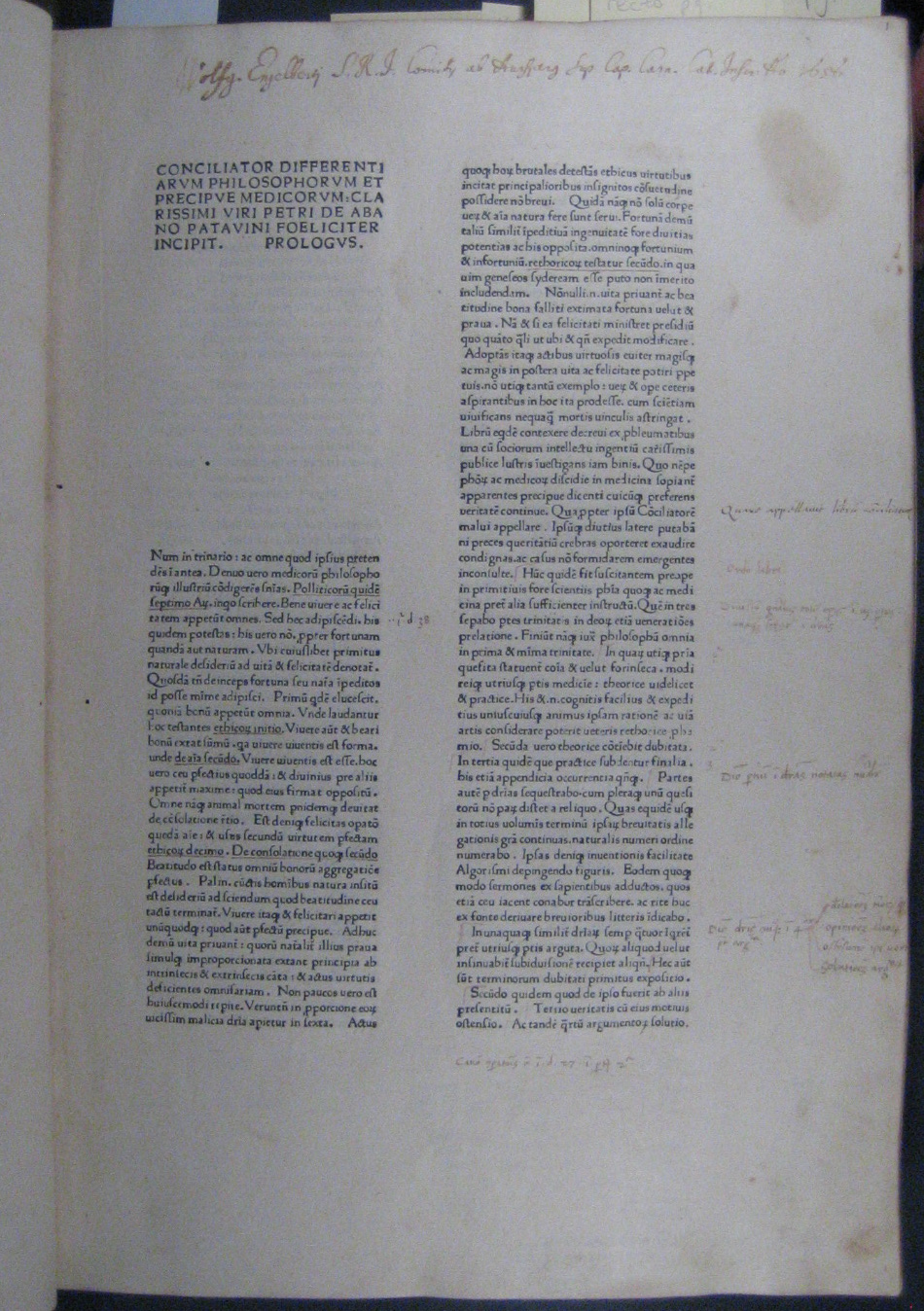

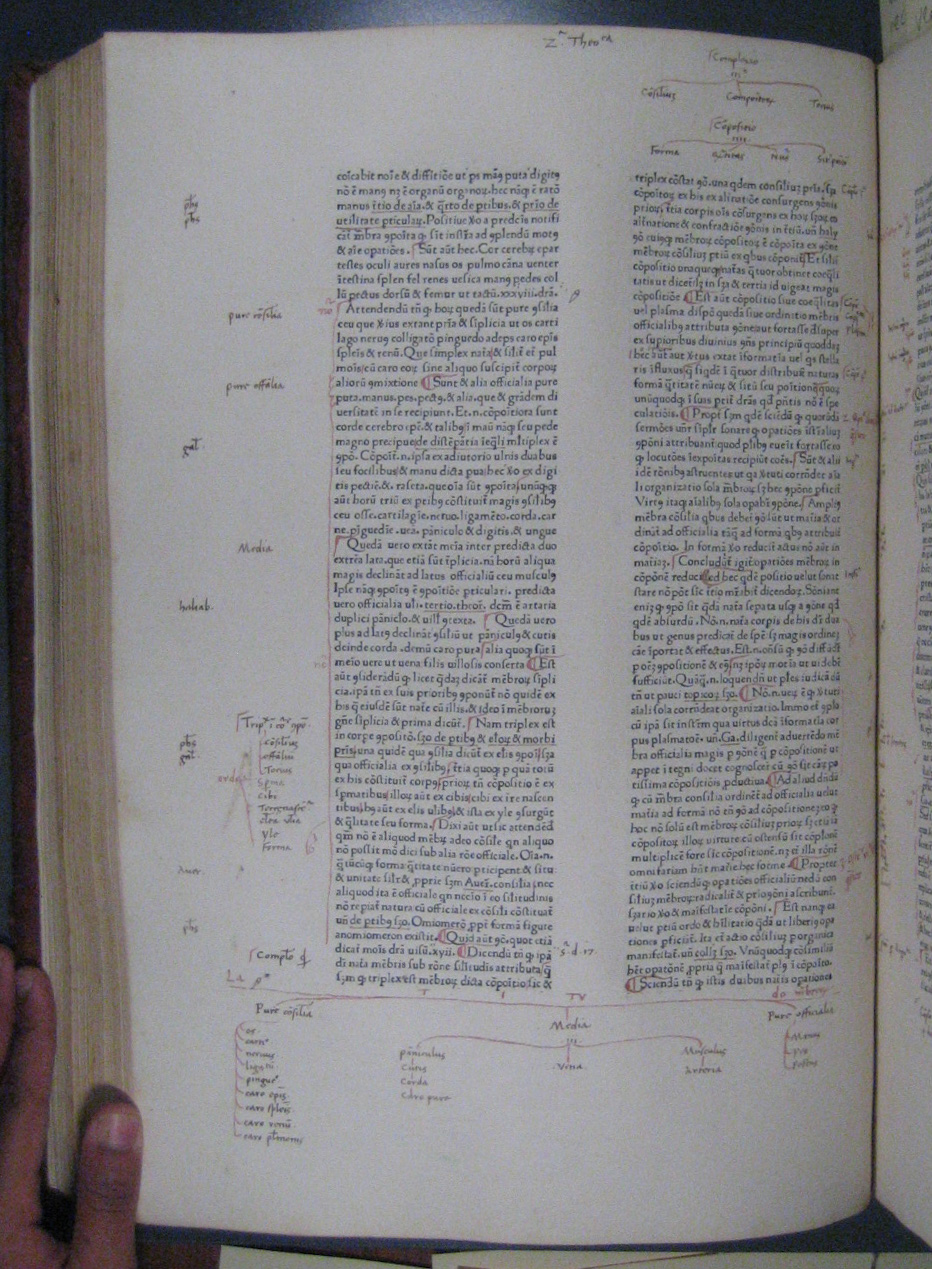

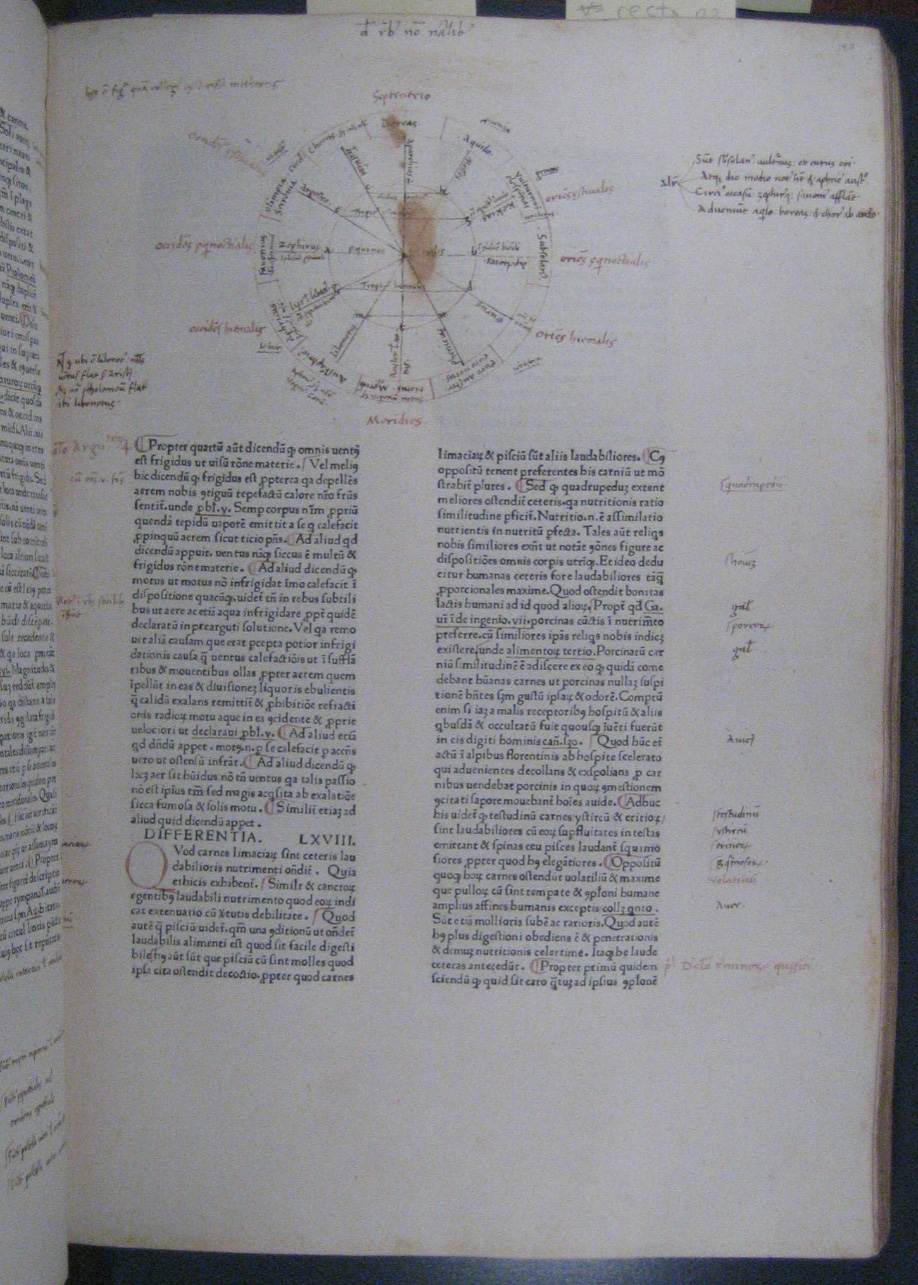

II + 532 + II ff., 320 x 225 mm, A – JJ4, KK5, Venice: Franciscus Argilagnes de Valentia, January 17, 1504.

Latin. Two columns. Blackletter, titles and text. Ornamented printed initials.

UCLA Young Research Library, Special Collections: *B765.A12C7 1504 BELT

On Piertro d’Abano see

[MB]

Contribution date: February 2016