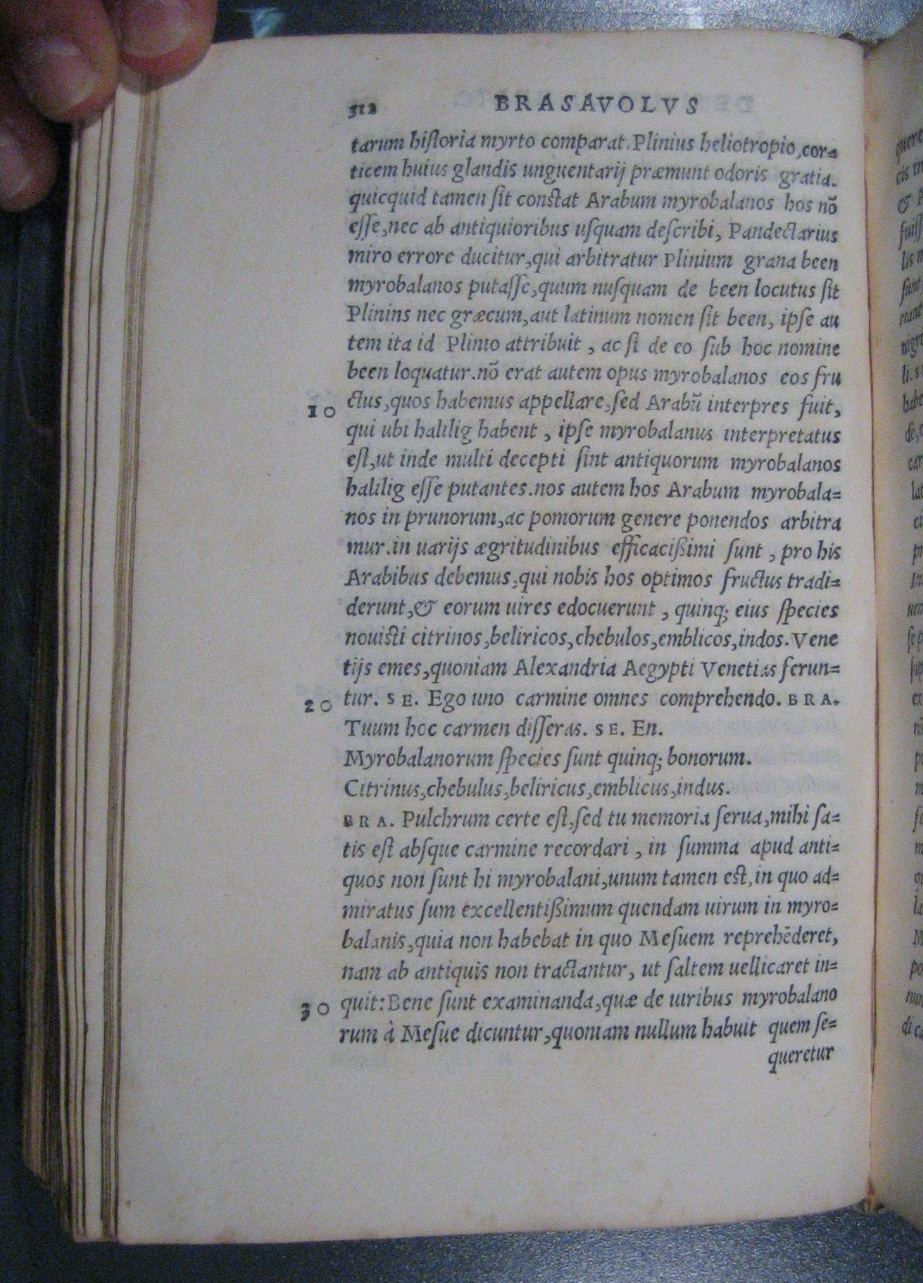

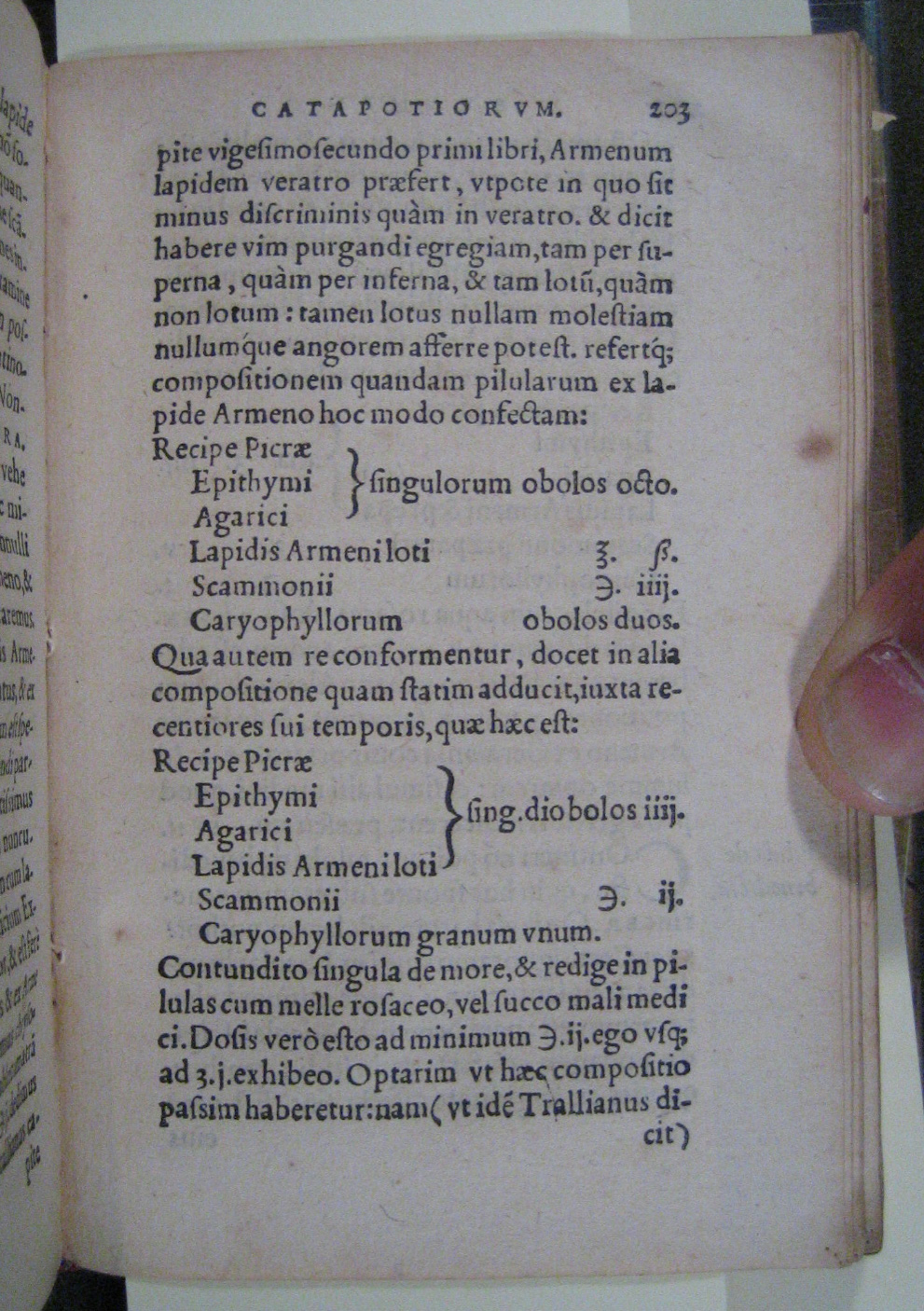

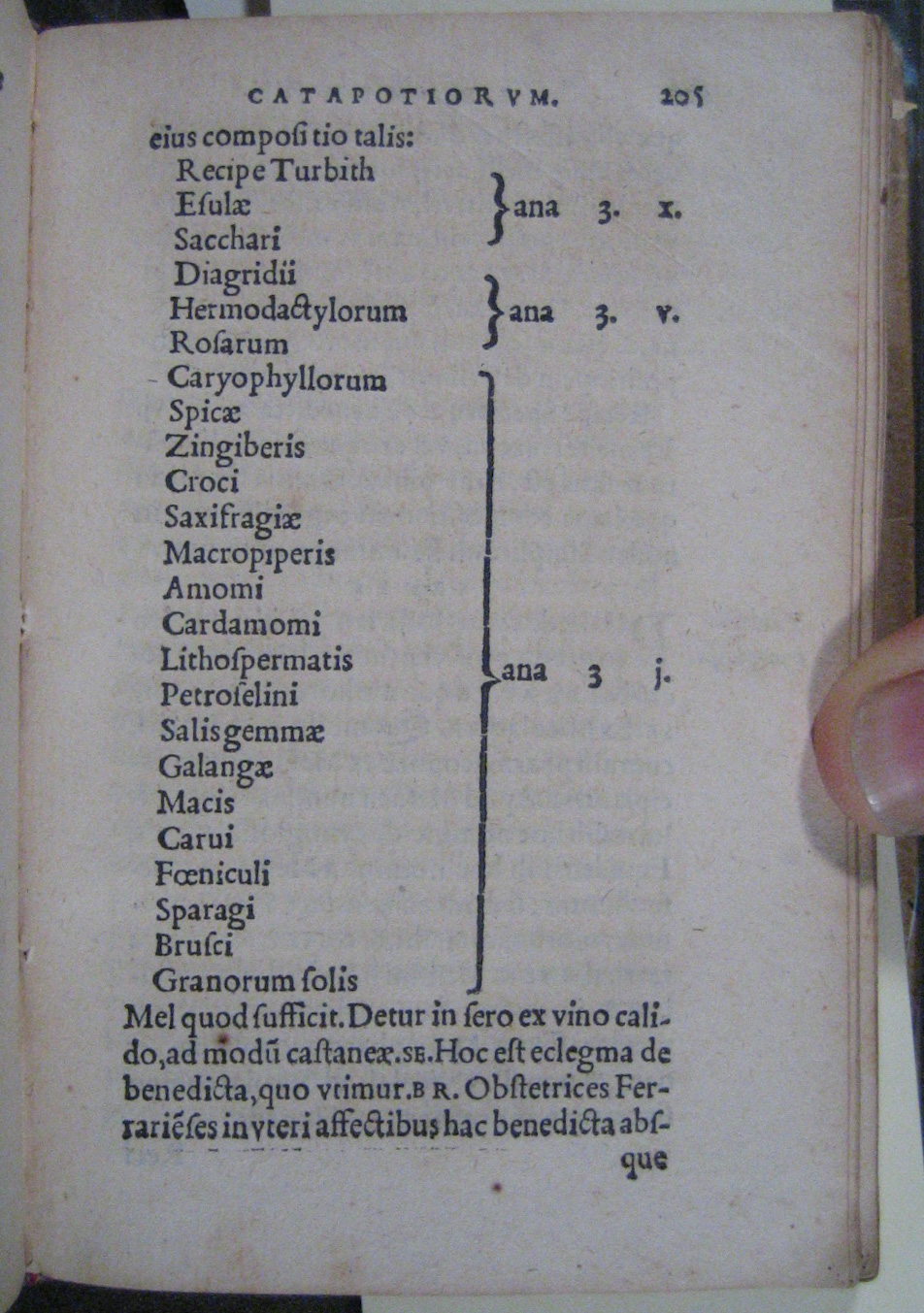

Leoniceno’s strategy did not have much immediate impact in Italy. Instead, it was adopted in Germany–though not until the late 1520s–by the physician Leonhart Fuchs who first wrote a volume on the mistakes of physicians in the vein of Leoniceno’s 1492 booklet which he published in 1530: Sixty mistakes of recent physicians, together with their refutation, for scholars (Errata recentiorum medicorum, LX. numero, adiectis eorundem confutationibus, in Studiosorum gratiam). Error 14, for example, was about theriac, originally used against snakes’ bites and further administered to treat any kind of medical condition. According to Fuchs, the theriacs of his time were not based on any science (Theriacae a nostri seculi Medicis certa non habent scientia). Error 19 denounced mistakes about poisonous plants, including those made by such a respected physician as Avicenna, who, according to Fuchs, seemed to have not known hemlock and aconite as he attributed to aconite the effects of hemlock (Avicenna Cicutam, Napellumque, herbas videtur ignorasse, quoniam quae Cicutae debentur, Napello tribuit). In Italy, Leoniceno’s strategy had its first application in the late 1530s, with one of his students, Antonius Musa Brasavola. Going beyond denunciation of mistakes in available literature, Brasavola toured the apothecaries in Italy to inspect the substances they used for the preparation of medicines and the medicines themselves, together with the formulae for these medicines.

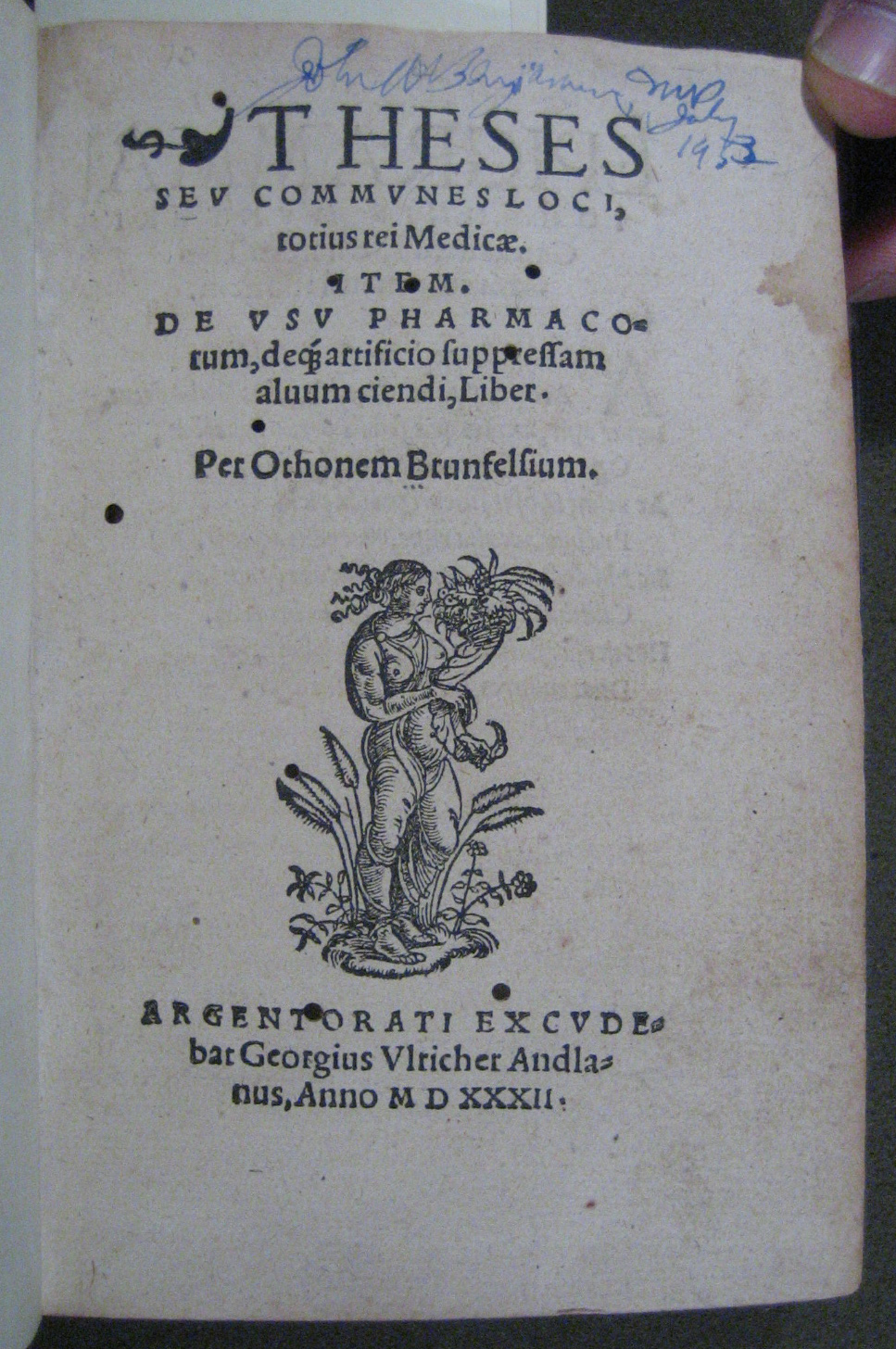

I+233+I ff., 148 x 98 mm, *5, a–F4, Strasbourg, Georgius Ulricher, 1532.

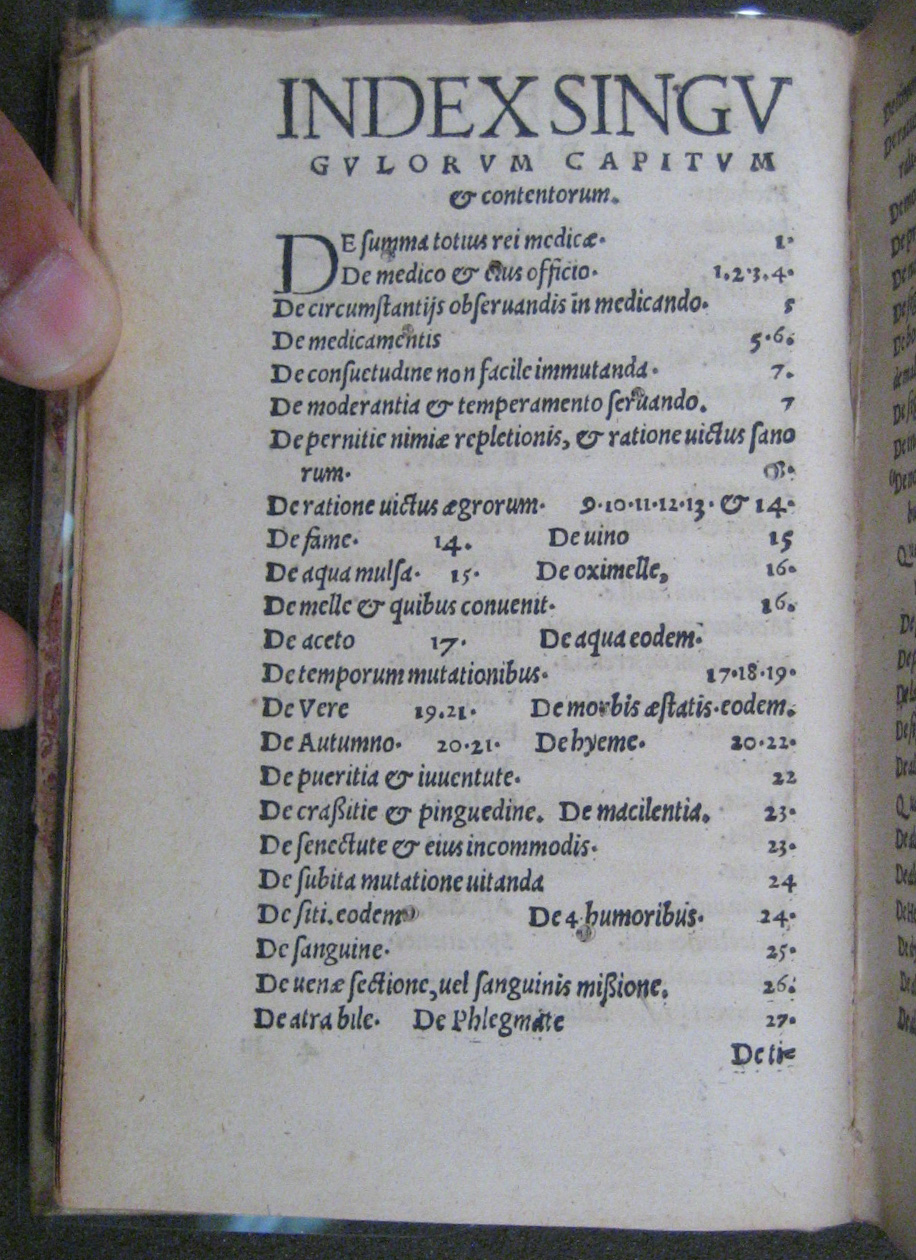

Latin. Full-page layout, mostly in roman type. Italic for index, marginal notes, epigram, errata, etc. Ornamental printed initials.

UCLA Louise M. Darling Bio-medical Library, Special Collections, Vault BENJ WZ 240 B835t 1532

After graduating from university, Brunfels (c.1489–1534) became a Carthusian monk in Strasbourg. However, in 1521, he quit the monastery, with the help of his friend Ulrich von Hutten, an outspoken critic of the Catholic Church, and when on to become a theologically controversial pastor in Steinau for 3 years. After this period, he returned to Strasbourg and founded his own school in 1524, and it was here that he prepared the first volume of his most influential book, the Herbarum vivae eicones, building on volumes of work he had done as a translator and compiler of medical texts. He received a doctorate of medicine from Basel University, having moved there around 1532, and was subsequently appointed as a physician in Bern. A year after this, in 1534, he died of an unknown illness. The Herbarum is notable not only for its text, but also its revolutionarily detailed illustrations by Brunfel’s associate in Strasbourg, Hans Weiditz.

“Brunfels, Otto”, in Charles Coulston Gillespie (ed.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1980, vol. 2, pp. 4–5.

Neues Deutsches Bibliografie [reference needed]

[JM]

I +630+ I ff., 170 x 110 mm, A-K4. Venice: Vincentius Valgrisi, 1545.

Latin. Full-page layout. Roman headings, italic body text. Some Greek interpolated.

UCLA Louise M. Darling Bio-medical Library, Special Collections, Vault: WZ 240 B736ex

A later edition of the opera which was originally published in two parts in Rome, 1536 and 1537.

Content: This text attempts to present the compete pharmacy of the classical period. It includes medicines derived from botanicals, animals, metals, earths and stones.

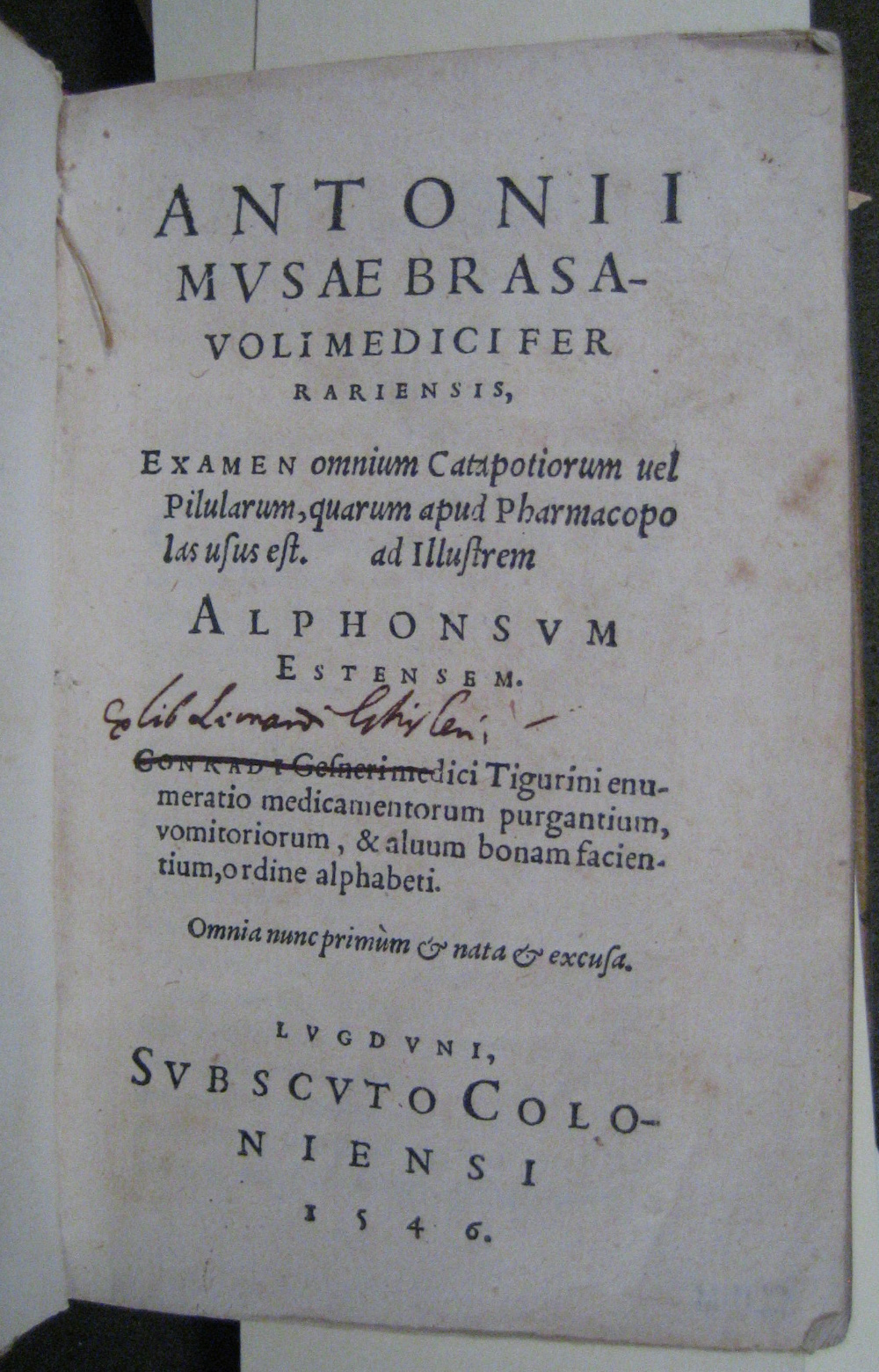

Antonius Musa Brasavola (1500-1555) was born in Ferara. He was to become one of the most celebrated botanists, physicians and consulting physicians of his time. Educated in Padua, Bologna and Paris, he received doctorates in law, medicine and theology. He became physician of Pope Paul III then Julius III and intervened as consulting physician in many celebrated cases including a serious illness of Charles V. Under the sponsorship and support of the Duke of Ferrara he wrote and researched this text. It was an effort to begin to revitalize and restore the classical medicine of Greece and to clarify and correct the “arbitrary” interpretations and mistaken identification present in traditional medieval medical practice. He died in Ferrara, July 6, 1555.

DBI vol.4, pp. 51-52; Who’s Who in Science 1st ed., 1968, p.232; A History of Magic and Experimental Science, Vol. V, 1941, pp. 445-471.

[SH]

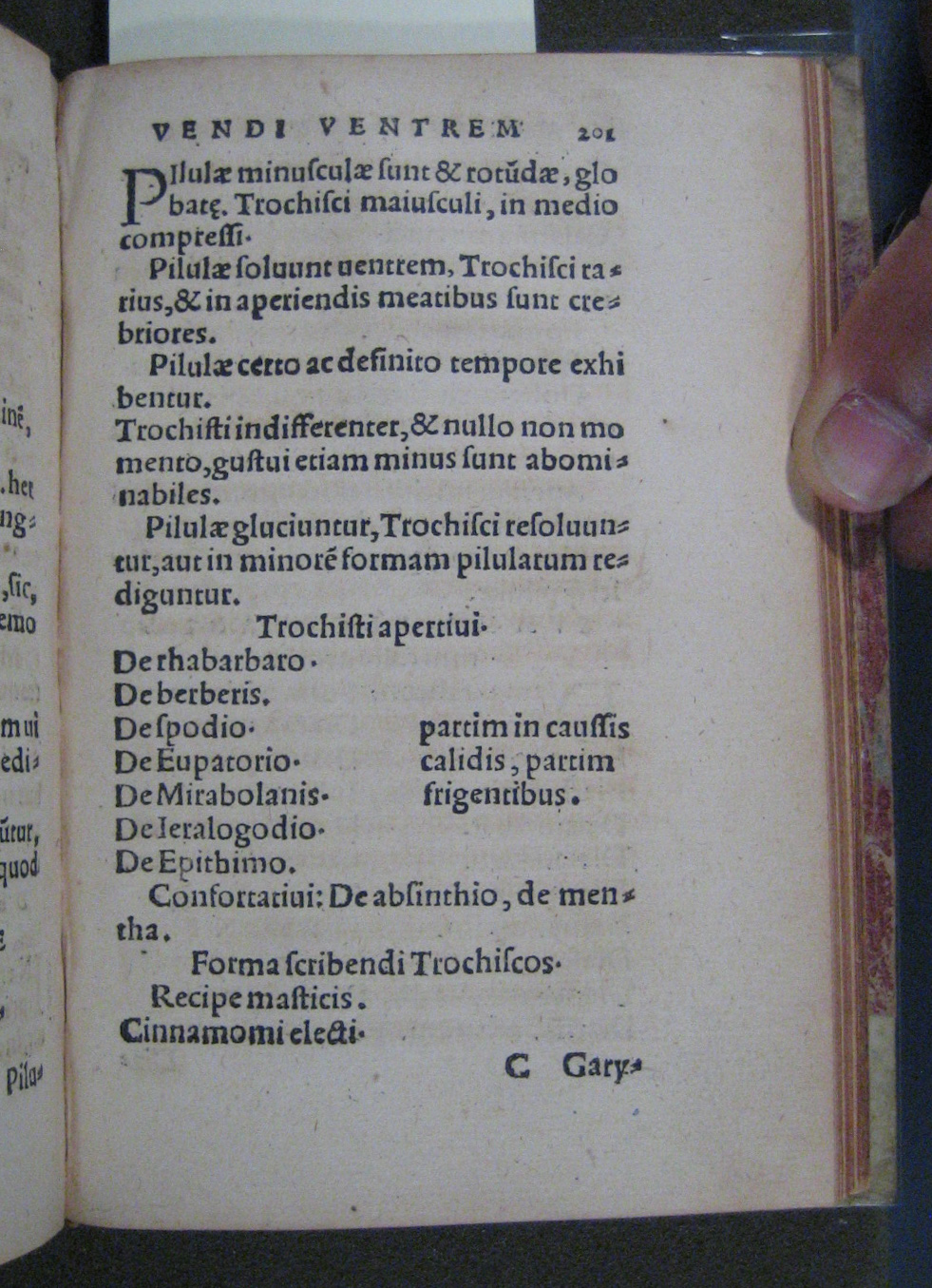

III +525+ I ff., 120 x 80 mm, Z-H4. Lyon, Frelloni fratres, 1546.

Latin. Full-page layout. Roman for the body text, italic for subheadings and marginal notes. Ornamental initials.

UCLA Louise M. Darling Bio-medical Library, Special Collections, Vault WZ 240 B736e

UCLA copy is bound with Bound with 6.4.

A later edition of the opera which was originally published in Venice in 1543.

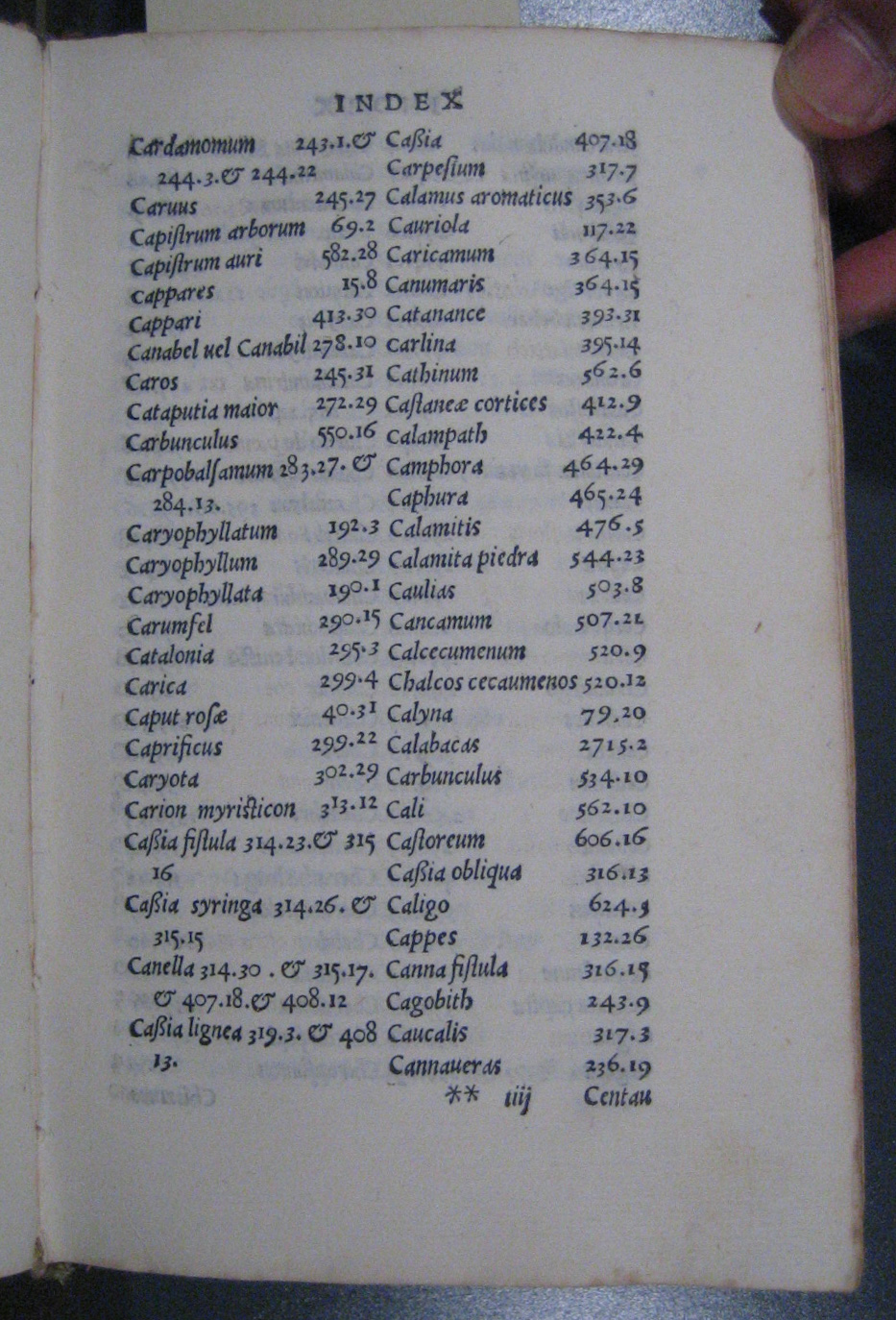

Content: The first text – Examan omnium catapotiorum – presents pharmaceutical recipes to compound a wide range of medicines. Examen syruporum presents additional recipes to compound pills and mix medicinal syrups.

[SH]

Latin. Full-page layout. Roman for the body text, italic for subheadings and marginal notes. Ornamental initials.

The work was first published in Lyon in 1540.

UCLA copy is bound with 6.3.

[SH]

Contribution date: February 2016